Dr. C.M. Johnston's Project

Discover McMaster's World War II Honour Roll

Harry G. Zavadowsky

Pilot Officer Harry Zavadowsky banked his twin-engined Bristol Blenheim and looked over his shoulder after completing his practice bombing run, better to see the results of his handiwork. As he did so, he may have inadvertently pulled up his aircraft, causing the engines to stall. Try as he must have in these desperate circumstances, he was unable to recover from the subsequent dive and crashed. He and the other two occupants of the plane were instantly killed. The date was 13 May 1942 and the place was the rural setting of Butcher's Farm, Thorney, near Peterborough, England. Harry had been serving in the air force for only a year and died before achieving his ambition to become fully operational. As the fates would have it, his was by no means an isolated incident in the training lives of air force personnel. Indeed, nearly 40 percent of the RCAF's fatal casualties abroad were not the result of enemy action.

Pilot Officer Harry Zavadowsky banked his twin-engined Bristol Blenheim and looked over his shoulder after completing his practice bombing run, better to see the results of his handiwork. As he did so, he may have inadvertently pulled up his aircraft, causing the engines to stall. Try as he must have in these desperate circumstances, he was unable to recover from the subsequent dive and crashed. He and the other two occupants of the plane were instantly killed. The date was 13 May 1942 and the place was the rural setting of Butcher's Farm, Thorney, near Peterborough, England. Harry had been serving in the air force for only a year and died before achieving his ambition to become fully operational. As the fates would have it, his was by no means an isolated incident in the training lives of air force personnel. Indeed, nearly 40 percent of the RCAF's fatal casualties abroad were not the result of enemy action.

Harry George Zavadowsky had been born in Hamilton, Ontario on 5 June 1919 to Peter and Emily (Mackowska) Zavadowsky, respectively natives of the Ukraine and White Russia, as those regions were then called. They had immigrated independently to North America, first to the United States and then to Hamilton, where they subsequently met and married. Harry and his younger brother, Joseph (Joe), were raised on Sherman Avenue North, neighbours and close friends of Charles [HR] and Harry Szumlinski, their early playmates on the street. The youngsters grew up in a distinctive and ethnically vibrant district lying near the heart of the city's sprawling industrial sector.

Unlike many of his neighbours Peter Zavadowsky was employed not in a local factory but as a butcher at a slaughterhouse and packing plant. But very much like his neighbours he was a hard-working and, to use that generation's phrase, a God-fearing member of the community and the Greek Orthodox Church. Fortunately he kept his job through the grim days of the Depression though some of the street's erstwhile breadwinners were not so lucky. But not surprisingly, his son Joe recalls that what his father had to endure in his long hours at the slaughterhouse often left him with reeking clothes and a keen distaste for meat. Nonetheless he and his wife went into the food-dispensing business, opening a restaurant on Barton Street close to their home. Emily Zavadowsky took over the management of the place, which became a popular neighbourhood rendezvous. While so engaged she expected her sons to do the household chores.

Like the Szumlinski children, Harry and Joe attended the nearby Gibson School on Barton Street. Their instruction was not confined, however, to those premises. Three days a week after school they also took courses in Ukrainian at St. Vladimir's Church, their parents' place of worship. Peter Zavadowsky was a firm believer in steeping his sons in their cultural heritage and had them taught Ukrainian dancing as well. It appears that Harry took less readily than Joe to the activity. Nor, for that matter, did either of the boys attend church as fervently as their parents though they put in a more or less regular appearance in the pews.

They also frequented the free circulating library, though not the services, at the nearby All People's United) Church on Sherman Avenue North. Among the popular books the Zavadowsky (and Szumlinski) boys borrowed was that generation's perennial favourite, Chums, an English publication full of derring-do tales of adventure and accounts of exploration, discovery and conquest in exotic lands. The Zavadowskys later recalled that they gained more from devouring that kind of reading material than from the conventional school fare. Moreover, it probably helped them along the road to that social and cultural assimilation experienced in due course by the offspring of immigrants.

Like most children in that north end neighbourhood the boys were expected to pull their weight. At the comparatively tender age of 8 or 9 Harry and his brother were put to summer work at a family friend's farm outside Waterford, near Simcoe. They continued to do so until well into high school. Even though the pay was "slim" they noticed that older people, usually city folk, often worked alongside them, only too thankful to get any kind of work in the Depression 'thirties. There was still time, however, for the boys to enjoy life on the street. Depending on the season, baseball and hockey were played there as well as at Scott Park and the Barton Street Arena. There were also more or less harmless street gangs to join, either neighbourhood or ethnic - Polish, Serbo-Croat, Ukrainian, and Italian. For the more daring there were "crap games", surreptitiously conducted in back alleys and then abruptly dispersed if the police put in an appearance. Harry apparently was marginal to this kind of activity, content with sports and less dubious diversions. This was not surprising because he took naturally to a variety of athletic pursuits, particularly after he graduated from Gibson School and moved on in 1933 to Hamilton Central Collegiate Institute, where many north end youth received their secondary education.

From the beginning Harry starred in football, first for the school's junior team and then for its senior squad, all under the appreciative eye of Captain J.R. ("Cap") Cornelius, Central's larger-than-life athletic director. Harry could play a variety of positions but his best was at left halfback, throwing "a mean forward pass" or plunging for good yardage, often "jaunting through the line", to quote an admiring Vox Lycei, Central's yearbook. In 1937 "Zavvy" helped HCCI win the Senior City Rugby Championship with what was called the "two-Harry combination". This was the so-called 91 play executed in harness with his "inseparable" friend, Harry Szumlinski. That same year and again in 1938, Harry and brother Joe represented HCCI on an all-star team, playing against other high schools in Toronto, an event sponsored by the Kiwanis Club. Both gave an excellent account of themselves and were awarded cups commemorating the occasions. But Harry still had to earn money to help support himself and his educational efforts. To that end he joined his father's workplace, toiling in the summers as a shipper and packer, that is, when he was not doing farm chore in Waterford.

Back at school, together with Charlie Szumlinski, Harry became an amateur thespian, performing in both opera and operetta and, in a lighter vein, in such farces as "Leave it to Psmith", one of the many offerings from the pen of the popular comedic writer, P.G. Wodehouse. Harry was lauded for his portrayal of a typical Wodehousian character, Lord Middlewick's secretary. He also tried out inter-room debating and, calling on his acting skills, performed creditably. In short, in the theatre and the debating forum, as well as on the playing field, Harry was no "shrinking violet".

While all his varied extracurricular activities drew him into the so-called majority culture, his father must have been gratified when Harry wrote an essay for Vox Lycei that clearly reflected the parental effort to keep the ancient heritage alive in the family. In his short piece, "The Ukraine", the 14-year old Harry proudly ranged from religion and national customs to clothing and diet, including the popular perohe (which his mother would serve in the family restaurant.) He tried to demonstrate that "Ukraine" was a distinctive cultural community and ought not to be lumped with "Soviet Russia" which was seeking to absorb it and eradicate its identity. "Someday", Harry concluded, doubtless echoing his father's thoughts, "Ukraine will again regain her independence". The young essayist did not live to see that process actually happen in the late 20th century.

In the fall of 1939, having moved on from HCCI, Harry registered at McMaster University, which had been transplanted from Toronto to Hamilton at the start of the decade. Once again a city youth - shades of Hank Novak [HR] and Jack Yost [HR] -- who could never have afforded university elsewhere in the province could take advantage of McMaster's proximity and live cheaply at home while gaining the advantages of a higher education. Because he was deficient in some of his high school work Harry was admitted to the General Course on the understanding that if he made good the shortfall he would qualify for the three-year Political Economy Option. This seemed the most appropriate course given his intention to go into "Business", as he announced on his application form.

Harry continued his athletic ways at McMaster, adding boxing and wrestling to his sports repertoire. In these activities the "feistiness" noted by some classmates came to the fore. Part of it may have been a response to the ethnic slurs which immigrants and their families often suffered at the hands of so-called mainstream society. At one point, in spite of the cultural sentiments once expressed in Vox Lycei, he became so frustrated that he contemplated changing his distinctive last name. But his concerned father and brother, keen on preserving tradition and defying bigotry, talked him out of it. It may be that Harry entered McMaster's boxing and wrestling programs - the ultimate in contact sports - in part to gain an outlet for his injured feelings. In any case, he soon made an impression in the boxing ring that matched his gridiron exploits, being one of two pugilists who excelled as freshmen. They provided, in the glowing words of the Silhouette, the student weekly, "the nucleus around which this [sophomore] year's boxing class will be built and an excellent foundation they will be if their performance of last year is to be taken as a criterion of their abilities as ring men". Harry and his partner easily lived up to the paper's expectations.

Unlike his extracurricular diversions military service on campus was compulsory, made so in the fall of 1940. This arose in response to what Chancellor Howard Whidden called the "blackness of the political horizon", caused by the recent fall of France and the threatened invasion of Britain by a triumphant Nazi Germany. In short order Harry, along with most male students, found himself on specified instructional days clad in khaki and taking drill in the ranks of the Canadian Officers' Training Corps. He was probably among the many who philosophically accepted it as another necessary, albeit unconventional, course to be added to their academic workload.

Meanwhile, in spite of his boxing laurels, football remained Harry's forte. In 1940 he was a valued member of the "cocky" Sophomore team that won the intramural championship and promptly rated itself "the class of the league". The Silhouette smirkingly made note of this: "The Soph team is good, just ask them". Harry, cocky or not, played his favourite position, left halfback, and was particularly adept at executing ground gaining extension plays. Had Varsity football been permitted in wartime all agreed that "Zav", as his teammates called him, could easily have become a standout in intercollegiate play. In any event, his efforts on the gridiron and in the boxing and wrestling rings earned him his 2nd Grade Athletic Colours at McMaster. To help finance his stay on campus, Harry, like friend Charlie Szumlinski, worked summers for the Canada Steamship Lines (CSL), in his case as a steward and waiter on the cruise ship, S.S. Noronic. He may well have met two other McMaster students on the ship, Nairn Boyd [HR] and Gordon Holder [HR], who also relied on the CSL for part-time employment. To his great delight Harry's earnings enabled him to buy an old Ford roadster, which must have considerably enhanced his social and recreational life. He was the first member of his family to own a car.

Harry was not to enjoy these amenities for long. Toward the end of his second year at McMaster - reminiscent of Hank Novak -- he decided to leave his studies and enlist in the air force. He had already given it a good deal of thought, having sounded out that service in the fall of 1940. When the RCAF subsequently requested to have his university status clarified and confirmed McMaster's registrar readily complied. The upshot was that on 7 March 1941, at his request, Harry's registration was formally cancelled with the cryptic notice that he had "gone into the RCAF". He had in fact done so four days earlier and been immediately dispatched to Toronto and its Manning Depot, housed in the yawning "Cow Palace" of the Canadian National Exhibition. He was about to enter a new world, the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, the Anglo-Canadian arrangement designed to provide qualified air crew for service overseas.

In Toronto Harry underwent what would soon become traditional at this stage of the training. He was subjected to drill, route marches, and musketry practice, all designed to endow him with what his superiors called "airmanship". There then followed medical inspections, inoculations, and rousing "pep talks" from the corporal or sergeant in charge. After two weeks of this regimen Harry was assigned for essentially more of the same at the RCAF's Picton station. Finally, in mid-May there was a posting to No. 3 Initial Training School at Victoriaville, Quebec, where he would be tested for the appropriate air crew role. He probably encountered and swapped stories with his old neighbourhood friend and fellow thespian, Charlie Szumlinski, who was about to complete his training on the station.

For many aspiring pilots like Harry, waiting for the results could be a traumatic business, and he was likely among those seized with the usual "pounding hearts and knotty nerves". To his great relief the matter was settled in his favour when he was selected for pilot training and allowed to climb further up the ladder, specifically to No. 16 Elementary Flying Training School, located at Edmonton, Alberta. He arrived there - his first visit to the West -- on a warm, sunny Dominion Day, 1 July 1941, for him a good omen as it turned out. He was trained on one of the station's standbys, the biplaned Tiger Moth, and successfully passed the tests. Even so, he confided the following to Charlie Szumlinski, then stationed at Trenton: "This is the toughest four weeks I've ever spent, But I've had a hell of a good time and some damned uncomfortable scares". Having learned that Charlie had washed out as a pilot trainee he told his friend that for old time's sake "I've done some rolls for you, they weren't very good but I'm getting thru". And get through Harry ultimately did. A month and a half after his arrival in Edmonton he was authorized to proceed southward to Calgary and to more advanced instruction at No. 3 Service Flying Training School (SFTS). There, starting on 26 August, it was the twin-engined Avro Anson trainer that would introduce him to the finer points of the art. Frequently, as was the custom at this SFTS, he was accompanied by a neophyte navigator out to prove his salt as well.

By early November, 1941 Harry had fully qualified on the Anson and was accordingly promoted sergeant - the usual procedure -- and awarded his coveted pilot's wings. A short time later, while on an embarkation leave visiting his family in Hamilton, a gratified Harry received word by cable that he had been officially appointed Pilot Officer on the strength of his skills and solid course standings. On that same leave he also paid a last wistful visit to a girl friend whom he had met at McMaster and frequently dated. He then departed for the RCAF's Y Depot in Halifax, the next step on the road to overseas and what was called the RAF Trainees' Pool. He left for England on 8 December 1941, the ship doubtless abuzz with the electrifying news that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor the previous day and brought the United States into what could now be called a genuine world war. He disembarked on the 18th, after the normal ten-day wartime crossing which had allowed for zig-zagging and other evasive manoeuvres designed to thwart the enemy's U-boats.

Following his arrival in England, Harry spent a month and a half at the Personnel Reception Centre in Bournemouth, in the company of other newly arrived airmen from overseas. This introductory stage came complete with medical inspections, assorted station duties, lectures from veteran RAF aircrew, and finally the issuing of flying kit and battle dress. On 29 January 1942, Harry was assigned to No. 3 Service Flying Training School, a prewar RAF facility located at Grantham, a large town in southwestern Lincolnshire noted for its engineering firms and agricultural fairs. Presumably the authorities who sent him there determined that he needed instructional reinforcement after his comparatively lengthy and training-free layover in Bournemouth. He was at the school for the better part of three months, taking a refresher course on the twin-engined Airspeed Oxford trainer. It may have been at Grantham, toward the end of his training session, that he had some free moments to reflect on what he wrote in his letters home, one of which was in Polish to Mrs. Szumlinski, whose hospitable home he had often visited. Apparently a recurring theme in his correspondence was the fortitude of the British people in coping with the varied calamities that had befallen them, including the ever present "Blitz", the Luftwaffe's nightly raiding sorties.

On 14 April 1942, with his refresher course behind him, Harry was posted to No. 17 Operational Training Unit (O T U / Excellere Contende), formed two years before at RAF Upwood in Huntingdonshire, a station equipped with Bristol Blenheims and Avro Ansons. Upwood was close by an auxiliary station, RAF Warboys, which, given its role, was a fitting name for the place. Actually Warboys was a corruption of an ancient Saxon name bestowed on what would ultimately become the large village in East Huntingdonshire that along with its neighbour, Upwood, would briefly become Harry's home away from home. Both communities were situated on high ground overlooking Peterborough and the “Great Fen”, that vast tract of low-lying often marshy land which extended into several English counties. For its part Warboys boasted, among other attractions, a 17 th century hostelry, which may well have served as the “local” for Harry and other members of 17 O T U.

Within two weeks he was involved in pre-operational training in the Blenheim, unaccountably nicknamed the "Blenburger", a light twin-engined bomber which had been used in a variety of roles in the early years of World War II. When not engaged in bombing enemy shipping and land targets it had served variously as a night fighter, a reconnaissance aircraft, a convoy escort, or as air support for commando raids on the Continent. Harry was destined to train on the Blenheim for less than a month. On 13 May 1942, he and his crew, Pilot Officer R.E. Corr and Sergeant J. White, both RAF personnel, embarked on their first practice bombing exercise. Apparently it was a tricky one. As the station's commanding officer later put it: "… taking into consideration the pilot's experience and the weather conditions [cloudy with a light wind] the exercise ordered was difficult but … such risks must be taken at an O.T.U if the Flight Commander considers the pupil 'Above average' ".

Thus commended, Harry duly took off in Blenheim V 5384, Mark IV, a more advanced model of the aircraft. After climbing to a thousand feet he leveled off and shortly dropped three of his seven bombs on the designated target at the base's Whittlesea bombing range. Then, as noted, disaster struck. The Blenheim, after completing this initial run, suddenly pulled up and then precipitously dived and crashed with the loss of all on board. The investigating officer subsequently reported:

Considers that the accident was caused by the pilot whilst carrying out his first bombing exercise beneath low cloud, stalled and lost control whilst executing a turn to the left after dropping his third bomb, possibly in an endeavour, as is customary to view the accuracy of the burst. (Emphasis added)

Obviously Harry was not the only fledgling bomber pilot eager to see the results of his run but for a tragic instant he may well have lost his concentration and hence the control of his aircraft. At the time all his family was told was that as "captain of a Blenheim" he had "for a reason not yet known crashed …."

Harry's name would join those of fellow north-enders Charlie Szumlinski and Hank Novak on McMaster University's burgeoning World War II Honour Roll. Besides his family the girl he had been dating before going overseas also received an official telegram with the devastating news. Obviously he had felt strongly enough about the relationship to list her along with his parents as the proper recipient of such a communication. To make matters even more poignant she had received hers on her 19th birthday, mistakenly though understandably assuming that it conveyed her "warm hearted beau's" best wishes for the occasion.

Harry's name would join those of fellow north-enders Charlie Szumlinski and Hank Novak on McMaster University's burgeoning World War II Honour Roll. Besides his family the girl he had been dating before going overseas also received an official telegram with the devastating news. Obviously he had felt strongly enough about the relationship to list her along with his parents as the proper recipient of such a communication. To make matters even more poignant she had received hers on her 19th birthday, mistakenly though understandably assuming that it conveyed her "warm hearted beau's" best wishes for the occasion.

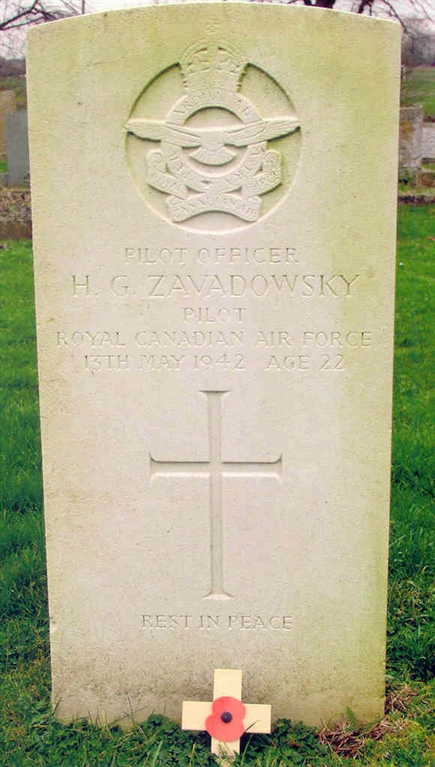

Harry George Zavadowsky is buried in Ramsey Cemetery, Ramsey, Huntingdonshire, England.

C.M. Johnston

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Joseph Zavadowsky (brother) kindly provided vital family information and documentation (designated JZ below). Also helpful in a variety of ways were John Aikman, Lillian (Szumlinski) Brillinger, Sean Edwards, Elizabeth Godard, Dale Heneberry, Brian Kedward, Kathleen (Zavadowsky) Land, Sue (McDowell) McPetrie, Norman Shrive, Mark Steinacher, Dolores Sudak, and Sheila Turcon. Sean Edwards, who was reached in England through Dale Heneberry (Joseph Zavadowsky's son-in-law), generously supplied welcome and corrective information about RAF Upwood and 17 O TU.

SOURCES: JZ: R.B. Richards to Peter Zavadowsky, 19 May 1942 (RCAF communication), Group Capt. John Kirby to Peter Zavadowsky, 12 July 1942 (RAF communication), RCAF Pilot's Flying Log Book, Pilot Officer Harry G. Zavadowsky, RCAF casualty telegrams addressed to Peter Zavadowsky.

National Archives of Canada: Wartime Personnel Records / Service Record of P/O Harry G. Zavadowsky and Precis of Proceedings of Court of Inquiry, Flying Accident; Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Commemorative Information, P/O Harry G. Zavadowsky; letter from Harry Zavadowsky to Charlie Szumlinski, 31 July 1941 (un the possession of Lillian Brillinger;on-line communication from Sean Edwards, 5 Oct. 2006; Hamilton-Wentworth Educational Archives and Heritage Centre: Vox Lycei (HCCI yearbook), 1933-4 , 44 (H. Zava[d]owsky, “The Ukraine”), 1934-5 (91), 1935-6 (43), 1936-7 (55), 1937-8 , 40, 41, 57-8: Canadian Baptist Archives / McMaster Divinity College: McMaster University Student File 7616, Harry G. Zavadowsky, Biographical File, Harry G. Zavadowsky (include admissions application and letter from McMaster Registrar to RCAF headquarters, 12 Dec. 1940; McMaster University Library / W. Ready Archives: Marmor , 1940 , 98 (107), 1941 , 37 (43, 105), Silhouette , 1, 18 Oct., 7, 14, 21 Nov. 1940, 13 Mar. 1941, McMaster Alumni News , 15 June 1942; Hamilton Spectator , 21 May 1942; Jean Martin, “The Great Canadian Air Battle: The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan and RCAF Fatalities during the Second World War”, Canadian Military Journal (Spring 2002), 67; W.R. Chorley, RAF Bomber Command Losses , vol. 7: O.T.Us, 1940-47 , 113 (entry supplied by Brian Kedward); Spencer Dunmore, Wings for Victory: The Remarkable Story of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in Canada (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1994), 81, 152, 350, 351; Blake Heathcote, Testaments of Honour: Personal Histories of Canada's War Veterans (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2002), 268-9 [Frank Cauley's recollections]; Les Allison and Harry Hayward, They Shall Grow Not Old: A Book of Remembrance (Brandon MA: Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum Inc., 2 nd printing, 1996), 842.

Internet: “History of Grantham”, www.rootsweb.com ; “Warboys”, www.genuki.org.uk/Warboys ; “No. 17 Operational Training Unit”, www.rafcommands.com/Bomber/17otu.html; “Bristol Blenheim”, www.rcaf.com/database/aircraft/blenheim.htm;

[ For related biographies, see Henry Eugene Novak, Charles Leonard Szumlinski, John Watson Yost, Franklin Charles Zurbrigg ]