Dr. C.M. Johnston's Project

Discover McMaster's World War II Honour Roll

Charles L. Szumlinski

"I am commanded by the Air Council", began a heart-stopping letter to Charles Szumlinski's parents, to express to you their grave concern on learning . that your son . is missing as the result of air operations on the night of 31 st July / 1 st August, 1942. Your son was navigator of a Whitley aircraft which . failed to return. This does not necessarily mean that he is killed or wounded, and if he is a prisoner of war he should be able to communicate with you in due course. Meanwhile enquiries will be made through the International Red Cross Society and as soon as any definite news is received, you will be at once informed.

"I am commanded by the Air Council", began a heart-stopping letter to Charles Szumlinski's parents, to express to you their grave concern on learning . that your son . is missing as the result of air operations on the night of 31 st July / 1 st August, 1942. Your son was navigator of a Whitley aircraft which . failed to return. This does not necessarily mean that he is killed or wounded, and if he is a prisoner of war he should be able to communicate with you in due course. Meanwhile enquiries will be made through the International Red Cross Society and as soon as any definite news is received, you will be at once informed.

This more or less standard message, dated 13 August 1942, did, to be sure, provide a slight ray of hope for the otherwise stricken Szumlinskis. But all too soon even that was extinguished when "definite news" subsequently arrived that their twenty-five year old son had in fact been killed on the operation in question.

Born in Hamilton, Ontario on 10 April 1917, Charles (Charlie) Szumlinski had been raised on Sherman Avenue, in the city's north end. In certain ways, as a local account points out, the area he grew up in was unique,

since, unlike other parts of Hamilton, its population was almost uniformly working class, which meant that economic circumstances were essentially the same for everyone and, consequently, the day-to-day problems of surviving were mutually understood and shared. Even after the ethnic mix began to change, this commonality . [was] sufficient to strengthen the forces that pulled the neighbourhood together.

Charlie's parents, Kazimierz and Stella (Walczek) were Polish immigrants who had made their separate ways to North America and ultimately met and married in Hamilton. They made their own contribution to the north end's "ethnic mix", joining with fellow Poles as well as with Ukrainian, Serbo-Croat, and Italian arrivals to form a distinctive neighbourhood. Polish as well as English was spoken in the Szumlinski home so consequently Charlie would often answer to the nickname Kaziu . His parents made every effort to keep much of the traditional culture alive, including sending their children to after-school Polish classes and subscribing to a Polish-language newspaper published in Buffalo, New York. All this, of course, had to do contend with the so-called mainstream pressures constantly brought to bear on the offspring of immigrants.

The assimilative process may have been helped along when the Szumlinskis departed from the traditional in one important respect by embracing Protestantism. Though he and his wife had been married in a Catholic ceremony the independently minded Kazimierz had broken with the Church over matters of ritual - the confessional for one - and, accompanied by his wife, had chosen to worship at the small All People's United Church only two doors from their home. In that day and age and in that place their newly adopted church, like others in the area, served not only as a house of worship but as a social and cultural centre. This was particularly true of its Sunday School and free circulating library, which acquainted Charlie and other young readers with the popular Chums books of English adventure tales. In a real sense All People's and its library, like the public schools the youngsters attended, were a social and cultural gateway to the larger world beyond their immediate north end neighbourhood.

Charlie's father was a core-maker at a nearby industrial plant, the International Harvester Company, the mother a housewife who shared with her husband the responsibility of bringing up Charlie and his three siblings, Harriet, Harry, and Lillian (approximate English versions of their given Polish names). The parents also found time to operate a confectionery store within a block of their home - indeed for a time the rooms above it constituted their home. The Szumlinski children and their neighbourhood friends, among them Harry [HR] and Joseph Zavadowsky, were habitués of the store; indeed the Zavadowsky boys often treated the Szumlinski home as their second one. Both sets of youngsters would remember the venerable stories of the old country and the opportunities and challenges of the new. They had fond memories of such youthful diversions as swimming in Lake Ontario, playing baseball in the street and at nearby Scott Park, and hockey at local rinks and the Hamilton Arena. On a photograph taken of him and two playmates at Burlington Beach, a joking Charlie later wrote, "the beginning of my athletic career."

Schooling, of course, was also an integral part of his life and another cohesive as well as assimilating force in the north end. Charlie's venture into formal education had begun at the Gibson School on Barton Street, a distinctive local landmark since the turn of the century - and now (2003) apparently doomed to be shut down. Early on the jovial Charlie proved a diligent pupil and a standout on the school playground, doing well at soccer and baseball. But it was at Hamilton Central Collegiate Institute (HCCI), which he began attending in 1932, that he truly shone in sports, primarily football and basketball, under the direction of the school's legendary athletic coach, Captain J.R. ("Cap") Cornelius.

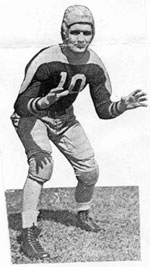

Central's yearbook, Vox Lycei , was soon full of Charlie's triumphs on the gridiron. His favourite positions alternated between middle wing and plunging halfback. He had the build -- standing 5' 11" and weighing some 170 pounds - to do justice to both and he took his toll of HCCI's football foes. "Charlie", exulted the sports editor in the 1934-35 yearbook, "is a good ball carrier and a hard worker . and excelled as both an offensive and a defensive player". But he was not just the athlete, however important that might have been. The same year, having joined Central's dramatic society, he also lent his strong singing voice to its operetta productions, his performances duly written up in Vox Lycei. In the 1934-1935 school year he continued his winning ways on both the football field and the stage, performing alongside his younger brother, Harry.

Central's yearbook, Vox Lycei , was soon full of Charlie's triumphs on the gridiron. His favourite positions alternated between middle wing and plunging halfback. He had the build -- standing 5' 11" and weighing some 170 pounds - to do justice to both and he took his toll of HCCI's football foes. "Charlie", exulted the sports editor in the 1934-35 yearbook, "is a good ball carrier and a hard worker . and excelled as both an offensive and a defensive player". But he was not just the athlete, however important that might have been. The same year, having joined Central's dramatic society, he also lent his strong singing voice to its operetta productions, his performances duly written up in Vox Lycei. In the 1934-1935 school year he continued his winning ways on both the football field and the stage, performing alongside his younger brother, Harry.

A sombre taste of things to come, however, was proclaimed in a lead article in the 1935-36 yearbook, entitled "This War Mad World". It was inspired by the rise of European and Asian dictatorships and their militaristic policies, a concern that prompted the editors to bring out a hopeful "Peace Issue" the following year. Even so, in spite of the looming spectre of war on the world scene, plenty of room was still found in Vox Lycei's pages for the usual round of student activities, including athletics and Charlie's varied achievements. These now included exploits on the basketball court where, playing a strong defence, he was instrumental in helping to win a championship for the senior boys' team. On the football field he continued to perform well, acquiring the unaccountable nickname,"Mur", and enjoying the honour of being elected captain of the senior squad. In short order he was also named to the school's prestigious Letterman Association and invited to its annual dances, attired formally in tails no less. He usually attended such functions in the company of a young woman friend and classmate, Thora Dean.

Again, however, Charlie mixed sports and related social activities with dramatics, performing in "Julius Caesar" and such light offerings as "All for Mary, A Comedy In Two Acts", written and directed by the versatile "Cap" Cornelius. He was also good-naturedly lampooned in Vox Lycei's section, "Strictly Personal", another mark of his solid standing at the school. Under his name the following was entered:

| Appearance |

Weakness | Favorite Pastime | Future Occupation |

| Hero | His Press Clippings | Acting | Dignified Buttling |

The last entry was inspired by his stage portrayal of butlers, first as Pots in "All for Mary" and then as Bellows in Central's production of P.G. Wodehouse's "Leave it to Psmith".

After matriculating from HCCI in 1937, armed with the Carr Trophy for studies and athletics, Charlie enrolled at McMaster University where he understandably listed as his principal referee the influential "Cap" Cornelius. The new freshman had followed the path of many a Hamilton student - Henry (Hank) Novak [HR] for one -- for whom McMaster was the only feasible and affordable alternative in that Depression era. Contemplating a career not in "buttling" but in business, the ambitious Charlie registered initially in Honour Political Economy. But in his second year he was obliged to switch to the Political Economy (Pass) Option when his grades fell below the required honour level. He had also promptly joined the Political Economy Club and in his final year served as its outside representative on other clubs, a tribute to his commitment and congenial ways.

When Charlie predictably went out for football, he met up with Nairn Boyd [HR], a fellow freshman and an equally gifted athlete -- and soon a close friend -- whom he would play alongside throughout his stay at the University. Charlie shared plunging duties with Boyd while doing battle in the intercollegiate intermediate league against such opponents as the "Aggies", the arch rival team that carried the colours of the Ontario Agricultural College. In his very first year, wearing the number 25 on his maroon and gray sweater, he made his mark. The student weekly, the Silhouette , happily reported that he was "a high scorer, hard working stalwart, and heads up player" on the team that won the Dominion Intermediate Rugby Championship. The following season, he was again - to quote the weekly - "in the best rugby condition" and, once more, along with Boyd, served as a productive plunging back and buttress for "Mac's hefty wing line". He was pleased to be named team captain that season, which replicated the honour awarded him in high school. He also received what may have been the ultimate accolade when he was described in the student yearbook, the Marmor, as "the football player's football player".

In spite of the time lavished on football Charlie did not neglect basketball, another prized sport dating from his days at Central. In his freshman year at McMaster he played on the intermediate squad and for his efforts, combined with those on the gridiron, he received the Athletic Award, 1 st Grade Colours. The following season he added to his laurels by playing as the captain of the senior basketball team. Taken together these exploits netted him an "M" certificate, qualifying him as a McMaster letterman. When interviewed years later, former classmates feelingly endorsed what a Marmor "Obit" had once said about him: "a student loved for his genial personality and respected for his hard, clean playing both on the football field and the basketball court". His impressed McMaster football coach remembered him, above all, as a "good natured but determined" person who "didn't know the meaning of the word 'quit'". In his last year Charlie rounded everything off by serving on the Men's Student Body Executive and continuing his ambassadorial work for the Political Economy Club.

Charlie worked part of the summer of 1940, probably with friend and teammate Nairn Boyd, as a waiter on the S.S. Noronic, a Canada Steamship Lines cruise ship that stopped at such places as Detroit, Sault Ste. Marie, and Port Arthur (Thunder Bay). But during his stint on the lakes Charlie advised McMaster - though no reason was given -- that he would not be returning to classes that fall. Perhaps he was contemplating joining up for military service. On the other hand, he may have been wrestling with an academic problem. That was later confirmed when he inquired about how he could "deal" with the work he had apparently deferred or failed in the previous session. From all accounts there was no mutually satisfactory resolution of this problem and as a result he had not qualified to graduate with his year. This is how matters would stand up to the time of his enlistment in the RCAF in early 1941. In the interval he took a temporary job as a receiving clerk at a previous employer, the large Canadian Westinghouse plant in Hamilton, not far from his home. He also tried out for the local football team, the vaunted Hamilton Tigers, and readily landed his favourite alternating positions, middle wing and plunging half. To no one's surprise he enjoyed a highly successful 1940 season as a Tiger "backfield star" in the Big Four League, which embraced, besides Hamilton, Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal.

A few weeks after the football season ended Charlie decided to enlist and duly became a fresh RCAF recruit. That event, which took place in Hamilton on 7 January 1941, was written up in the Hamilton Spectator under the heading, "Seeking to Drop-Kick Hitler". The piece mused that "If [Charlie] breaks through the Siegfried line [the German defense system] in the same manner that [he] did through the [Toronto] Argonauts . Herr Adolf [Hitler] better go to the bench and make room for a substitute". With that kind of send-off and with the enlistment procedures completed, Charlie then followed the route taken by all aspiring McMaster airmen. First, there was the introductory session at a manning depot, in his case Toronto's, which was housed in the CNE's Coliseum, the celebrated "Cow Palace". The cavernous building would play host to him and hundreds of others for two weeks of drilling, musketry practice, and route marching, all part of the "airmanship" their instructors sought to instill before their charges actually became airborne.

Then on 22 January it was on to Picton, on the picturesque Bay of Quinte, for what appears to be more of the same regimen at No. 1 "A" Manning Depot. For the two weeks Charlie was there he may also have done the customary guard duty allotted all new recruits. Tarmac duty (a euphemism for manual labour) may also have come his way. (In the spring, some two months after his departure, the station was turned into a bombing and gunnery school.) From Picton he was moved on next to No. 1 Wireless School at Montreal. There, beginning on 5 February 1941 and over the space of some two and a half months, he received basic instruction in the technology on Norseman and Tiger Moth trainers. That stage completed, he was assigned on 23 April to No. 3 Initial Training School (ITS) at Victoriaville, Quebec. This was the so-called first hurdle that every prospective flyer had to surmount if he ever wished to become truly airborne. In common with others, No. 3 ITS would test and sort Charlie and other recruits into various aircrew slots, ranging from pilot through navigator to wireless air gunner. His path might well have crossed that of his old neighbourhood friend, Harry Zavadowsky [HR], who arrived on the station just two weeks before he left for other duties.

While stationed at Victoriaville Charlie's thoughts briefly turned to McMaster and the problem of his academic standing. Having learned that some of his fellow trainees had received their degrees without having to write final examinations, he sat down in late April 1941 and wrote a letter to the registrar. "I know for a fact", he pointedly stated,

that students from other leading Canadian universities who have not finished their courses, and are now serving the great cause are being granted their degrees so I don't think my Alma Mater should make an exception of me .. [A]s I may be overseas by next fall, I'd like to have this attended to as soon as possible.

However much it regretted the situation, McMaster did not see it that way, pointing out to Charlie that he had previously missed or failed work and therefore did not qualify. Had he passed that work and achieved creditable class marks in his last year, which would have excused him from the final examinations, then and only then would he have been eligible to graduate. Charlie's response to the McMaster regulation has gone unrecorded. In any event, he had little time to fret because he was soon fully involved in a demanding round of training exercises.

On 28 May 1941, having been selected for pilot instruction at Victoriaville, a gratified Charlie was en route to Windsor Mills, Quebec, and No. 4 Elementary Flying Training School. Now he would have an opportunity to go aloft for the first time as a student pilot in a Tiger Moth or Finch trainer. His hopes and enthusiasm were rudely cut short, however and like so many aspirants at this pivotal stage, he was unceremoniously "washed out". In his case it would appears that a critical depth perception problem had ruined his chances of safely landing an aircraft. In any case he was dispatched on 22 June to the Composite School at Trenton, Ontario, the RCAF's principal training station. Among other things, the school was a kind of dumping ground or, to put a better face on it, a re-mustering place for all those unfortunates who had failed their flying tests. Norman Shrive, an airman who did his guard duty there, recalled just how despondent and demoralized this fallen group could be, many of whom had set their hearts on handling the controls of a warplane and were now being sorted out for less desirable (and supposedly less glamorous) aircrew or even ground crew positions. If Charlie, who usually took adversity in his stride, shared the general malaise he gave no sign - at least so far as is known.

At any rate, he spent the better part of two uncertain months cooling his heels at Trenton. He whiled away some of the time writing family and friends, including Harry Zavadowsky, who was presumably told of Charlie's misfortunes as a pilot trainee. "Damned glad to hear form you", Harry replied from Edmonton, Alberta, where he was undergoing Charlie's training experience. "I'm going for my last 50 hours check out [?] over the weekend", he told his friend. "f I don't pass I'll be seeing you [in Trenton]. If I get thru' I'll be going on Harvards [trainers], at least that's what my instructor said". For his part, Charlie was eventually assigned to No. 5 Air Observer School, which had been opened earlier in the year at Winnipeg, Manitoba. If he could not be a pilot, he could at least, if all went well, serve as a navigator, perceived by many as the next best thing in aircrew anyway. His proud sister, Harriet, who had done her bit to keep up his spirits during what must have been a stressful time, wrote him that "I'm sure that . one 'Charlie Szumlinski'. [will] "be a Whizz at the Observer work . and that's no fooling". A friend, who was also in the service, said much the same, assuring "Szum" that "any course they have is a cinch for you". Besides, he added, "you'll be wearing an officer's uniform too", a prediction that would make good.

Charlie arrived in Winnipeg on 18 August 1941 and may well have experienced what so many other trainees did: the friendly, generous, and hospitable welcome its citizens invariably lavished on these grateful but weary rail travelers. After successfully completing his navigational training on 8 November - mainly on the course workhorse, the twin-engined Avro Anson -- Charlie was dispatched to No. 7 Bombing and Gunnery School, also located in Manitoba at Paulson. There he was instructed in the fine points of another essential function of the navigator, dropping bombs on enemy targets. Some six weeks later, just days before Christmas, 1941, he left for Rivers, Manitoba where he started an intensive astro-navigation course at No. 1 Air Navigation School. Charlie may have shared other trainees' distaste for Rivers, whose only saving grace apparently was its proximity to the more amenable municipality of Brandon, especially at a time like Christmas. The Rivers course, mandatory for all navigators bound for overseas duty, would also be taken by another former McMaster student, Franklin Zurbrigg [HR], before he embarked for the air wars. Soon enough that would be Charlie's destination as well.

On 20 December 1941, having successfully qualified for aircrew, a gratified Charlie was, first of all, promoted sergeant and awarded his Observer wing and then early in the New Year appointed Pilot Officer. Just two days later, on 21 January 1942 he was dispatched to the RCAF's Y Depot in Halifax to await embarkation for the United Kingdom. Thora Dean, who had accompanied him to McMaster and become his fiancée, had wanted a wedding before he departed but a prudent Charlie had prevailed upon her to wait until his return. In late February, when shipping became available, he set sail and after the usual ten-day crossing arrived safely at his English destination, a piece of news he immediately cabled to his relieved family. A new and ultimately more dramatic phase of his military service was about to begin. After spending considerable time at the Personnel Reception Centre in Bournemouth where, among other things, he underwent medical checks and was issued flying kit and battle dress, Charlie was routinely assigned to the Air Force Trainees Pool. In late April 1942 he was sent to No. 9 Advanced Flying (Observer) Unit, which was located near a Welsh coastal town, distinctively named Llandwrogg. There he undertook what amounted to a refresher course on the Anson, the aircraft he had flown in as a trainee in Canada.

After a month of this instructional reinforcement in Wales Charlie was dispatched, so to speak, to the front line. On 29 May 1942, doubtless in a considerably excited state, he arrived in the Cotswolds village of Honeybourne. (Apparently Charlie, like Franklin Zurbrigg, kept a wartime diary that may have revealed a good deal about his responses to such situations but unfortunately its whereabouts are unknown). Honeybourne is located in Worcestershire, and was the site of Bomber Command's No. 24 Operational Training Unit (Cum Labore Adjuvantes / O T U). The station had originally been designed to train ferry pilots but in March, 1942, some two months before Charlie arrived, it was turned into a bomber base where hitherto unvetted aircrew could be trained on the job in actual operations. No. 24 was situated in the picturesque Vale of Evesham and moreover within easy reach of renowned Cotswolds pubs, a boon for off-duty servicemen. The station was in the heart of what one airman called a "rich landscape", dominated by fruit orchards and market gardens, a scene that may have reminded Charlie of the Niagara country at home. The orchards stood out, as another arriving trainee noted, in marked contrast to the "ugly black bulk" of the aircraft in which he -- and Charlie -- would fly, the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley.

The Whitley (for short) was a twin-engined medium bomber, which had seen service in Italy and over Germany (mainly dropping propaganda leaflets) in the early months of the war. It carried a crew of five, had a top speed of 230 mph, was armed with machine guns in powered turrets fore and aft, and could transport up to 7000 lbs. of bombs. In April 1942, however, some six weeks before Charlie joined No. 24, the Whitley had been withdrawn from first-line service, replaced by the clearly more powerful and effective twin-engined Vickers Wellington, and relegated to operational training units like his. While some pilots appreciated the Whitley's easy handing others described it as a "clumsy cow" or, even more graphically, as the "Flying Coffin". One Canadian had good cause to question its serviceability when he saw two Whitleys blow up over the airfield, the gun turret of one actually plummeting on the nearby village of Broadway.

All the same, when circumstances demanded, otherwise dubious Whitleys and the OTUs would be pressed into service, especially when Bomber Command laid on a series of record-breaking raids commencing in the spring of 1942, to which every available crew and aircraft were urgently assigned. That would be Charlie's lot in late July 1942 when such a raid was planned for Dusseldorf in the heart of the industrial Ruhr. By this time he had already spent some six weeks being familiarized with the workings of the Whitley, mainly through so-called cross-country exercises. In all, some 630 aircraft were to be deployed over Dusseldorf and its environs. This did not match the first-ever 1000 bomber effort directed at Cologne just two months earlier but it was formidable enough. Charlie would be navigating one of the 24 Whitleys assembled for the attack -- as it turned out, the smallest segment of the raiding force. Over two-thirds of it would consist of Wellingtons and powerful four-engined Avro Lancasters. He and his fellow crew members would thus be in impressive company when their Whitley Z9512 took off for Dusseldorf just before midnight on 31 July 1942.

According to Dusseldorf's own records – cited in Bomber Command War Diaries -- some 300 of its people were killed, over a thousand injured, and nearly 12,000 rendered homeless in the subsequent raid. Nearly a hundred major fires were started and most sections of the city were struck. There is no account given, however, of damage to industrial plant or military targets as such. The bomber force also paid heavily as had others in recent nights. In this case the losses were set at over 4% -- just barely acceptable -- 29 aircraft altogether, including two unfortunate Whitleys.

One of them, Z 9512, navigated by Pilot Officer Charles Szumlinski, was destroyed by “hostile defenses in the target area” – quite possibly night fighters -- either on its way to or over the objective. In any case, it went down over German territory with the loss of four of the five aircrew on board. The pilot, Flight Lieutenant William Anthony Bispham (a.k.a. Anthony Wm. Thompson) survived and was taken prisoner though later in the war, after several attempted escapes, he was summarily shot in a Nazi concentration camp in Poland. Meanwhile his navigator, the “always extremely popular” Charlie -- the Alumni News' words -- was, as noted, initially reported missing and then subsequently declared killed in action. He and his crewmates had been well aware that they were taking part in the opening phases of an historic air offensive, the only means Britain then had to carry the war to the heart of Nazi Germany. Thus “Charlie died”, to quote one of his close air force friends, “realizing his one ambition, to make [her] pay for this suffering of mankind”.

The Szumlinski family received letters of condolence from many and varied quarters, including McMaster University. Professor Togo Salmon, the classicist, wrote them about "your boy Charlie" the day after he spotted the casualty notice in the local newspaper. "All of us on the staff", he assured them, "held him in great affection and esteem", a sentiment strongly echoed by Chancellor George Gilmour. "I remember your son so well", he wrote, "that it is only with a sense of unreality that I can write about him as gone". Sympathy messages also poured in from friends and fellow servicemen, and from the HCCI Lettermen's Association, the Gibson School, and the McMaster alumni. But perhaps the most poignant came from a younger Sherman Avenue neighbour: ". I often used to meet Charlie going from Central Collegiate and always got that ready smile to show he had not forgotten me as he grew older".

All these condolences and reminiscences were passed on to an equally sorrowing Thora Dean, who had done her own wartime bit by serving with the Women's Auxiliary Air Force. The same held true for Charlie's siblings, Harriett and Harry, both of whom served overseas. Harriett joined the Canadian Women's Army Corps and was ultimately appointed an interpreter with the Polish exiles flying with the Royal Air Force. Harry meanwhile served in Italy as a lieutenant with the Perth Regiment of Canada. Fortunately both survived the war.

Charles Leonard Szumlinski is buried in Reichswald Forest War Cemetery, Kleve, Germany.

C.M. Johnston

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The following generously contributed to this biography by providing leads, information, reminiscences, documentation, or archival assistance: Dominic Bispham, Lillian (Szumlinski) Brillinger, James Cross, Margaret Houghton, Brian Kedward, Jane (Szumlinski) McManus, Sue (McDowell) McPetrie, Trevor Meldrum, Michael Milos, Irene Paradisi, Robert Philip, Patricia Radley-Walters, Gordon Ramey, Norman Shrive, Mark Steinacher, Dolores Sudak, Madeleine Szumlinski, and Joseph Zavadowsky. Lillian Brillinger kindly furnished recollections of her brother and key family information together with important documentation (see LB below). Dominic Bispham identified the Whitley's pilot as his grandfather and told of the latter's abortive escape attempts and subsequent execution.

SOURCES: LB: Wartime letters, postcards and photographs of Charles Szumlinski et al (including family members, friends, fellow servicemen, and school and university officials whose correspondence is quoted in this biography) and such memorabilia as Souvenir Programmes, Central Collegiate Dramatic Society ; Hamilton Public Library / Special Collections: Lawrence Murphy, Philip Murphy, Tales from the North End (Hamilton: Permanent Press, 1981), 53, 103-4, Vox Lycei (HCCI), 1934-35 , 58, 61, 1935-36 , 10, 79, 1936-37 , 52, 54, 55, 61, 75, 1937, 40, 1937-38 , 32, 42; Canadian Baptist Archives / McMaster Divinity College: McMaster University Student File 7270, Charles L. Szumlinski (admissions application, course results), Biographical File, Charles L. Szumlinski (includes letter from A.C.2 Charles Szumlinski to McMaster Registrar, undated); McMaster University Library / W. Ready Archives: Silhouette , 6 Oct. 1938, 3, 6 Oct. 1939, 1, 13 Oct. 1939, 1, 10 Nov. 1939, 1, Marmor , 1937-38 , 34, 1938, 46, 1938-39 , [100], 1940 , 32, 65, 110; McMaster Alumni News , 20 Feb. 1942, 15 Oct. 1942, 20 Feb. 1943; Hamilton Spectator , 9 Jan. 1941, 11 Sept. 1942; Canadian Football Hall of Fame & Museum: Programme , The Tiger Team of 1940 , 9, 37.

National Archives of Canada / Wartime Personnel Records: Service Record of Pilot Officer Charles L. Szumlinski (includes letter from Kingsway, RCAF Headquarters, Ottawa, to Mrs. S. Szumlinski, 13 Aug. 1942); Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Commemorative Information, P/O Charles L. Szumlinski; Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum / Library: Brian Kedward, Angry Skies Across the Vale (Evesham [England]: the author, 1996 [an autographed history of No. 24 O T U]), 6, 7, 18, 27, 31, 74, 91, 92, 96, 97, 98, 102, 103, 104, 359; Martin Middlebrook and Chris Everitt, The Bomber Command War Diaries: An Operational Reference Book , 1939-1945 (London: Penguin, 1990 ed.), 292, 300; W.A.B. Douglas, Brereton Greenhous et al, The RCAF Overseas , III: The Crucible of War, 1939-1945 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986), 592, 593, 615; W.R. Chorley, Royal Air Force Bomber Command Losses, vol. 7: Operational Training Units, 1940-1947 (Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing, 2002), 140; (Les Allison and Harry Hayward, They Shall Grow Not Old: A Book of Remembrance (Brandon, MA: Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum Inc., 1996, 2 nd printing), 369, 744; Bill Hockney and Moe Gates, eds., Nadir to Zenith: An Almanac of Stories by Canadian Military Navigators (Trenton ON: the editors, 2002), 9 [James Ivor Davies, “Prairie Kid to POW”]; Spencer Dunmore, Wings for Victory: The Remarkable Story of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in Canada (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1994), 193, 213, 217, 235, 349, 333-5, 354, 356, 357, 360.

Internet: www.rcaf.com/database/aircraft/whitley.htm: “Armstrong Whitworth Whitley”.

[ For related biographies, see Albert Harry Mildon, Henry Eugene Novak, Harry George Zavadowsky ]