Dr. C.M. Johnston's Project

Discover McMaster's World War II Honour Roll

J. Gordon Sloane

A Toronto native, James Gordon Sloane was born on 22 April 1920 to Algus and Marion Sloane. The father, a bank manager, was subject to transfer to different branches and as a result the family lived in several communities before settling in Hamilton. Thus Gordon (usually addressed as Gord) went to public school in Stratford and received part of his secondary school education in Woodstock before going on to complete it at Delta Collegiate Institute (DCI) in Hamilton's east end. There the family had taken up residence on Fairleigh Crescent and joined McNab Street Presbyterian Church. The father was an avid outdoorsman - an antidote perhaps to a bank's close confines -- and before long Gord and his siblings, Donald, Jeannette, and Douglas, were introduced to that invigorating life, particularly at the northern island cottage the family frequented during the summers. Swimming, canoeing, boating, hiking, and horseback riding were among the strenuous activities in which Gord and the others soon became adept. Indeed, Gord revealed a good deal about himself and his liking for the trails when he hung a framed motto in his room at home: "Learn To Ride The Horse That Threw You".

A Toronto native, James Gordon Sloane was born on 22 April 1920 to Algus and Marion Sloane. The father, a bank manager, was subject to transfer to different branches and as a result the family lived in several communities before settling in Hamilton. Thus Gordon (usually addressed as Gord) went to public school in Stratford and received part of his secondary school education in Woodstock before going on to complete it at Delta Collegiate Institute (DCI) in Hamilton's east end. There the family had taken up residence on Fairleigh Crescent and joined McNab Street Presbyterian Church. The father was an avid outdoorsman - an antidote perhaps to a bank's close confines -- and before long Gord and his siblings, Donald, Jeannette, and Douglas, were introduced to that invigorating life, particularly at the northern island cottage the family frequented during the summers. Swimming, canoeing, boating, hiking, and horseback riding were among the strenuous activities in which Gord and the others soon became adept. Indeed, Gord revealed a good deal about himself and his liking for the trails when he hung a framed motto in his room at home: "Learn To Ride The Horse That Threw You".

Meanwhile, his younger brother, Douglas, had good reason to remember one vacation incident. When he fell afoul of an axe while building a tree house, he was rescued by Gord and speedily "piggy-backed" home to the cottage. Their father quickly applied a tourniquet before having Douglas shipped to the nearby mainland hospital. Clearly the younger brother was impressed by Gord's quick-thinking on that long-ago occasion. So were other members of the family. Further, while conceding that Gord was no "goody-goody two shoes" they also warmly recalled his positive approach to life, which earned him much "respect and admiration".

In the three years he spent at Delta Collegiate, 1936 through 1938, Gord seemed, on the whole, to make an easy adjustment to the city high school's way of doing things. When it came to school dances, however, his shyness initially ruled out a regular "date" but without any hesitation he was more than happy to rely on sister Jeannette to do the honours. Having long treated him as a virtual twin brother, whose company she always enjoyed, she had no problem with the arrangement either. Indeed, as she recalled, "we had a lot of fun" doing the "light fantastic." She also enjoyed his jokes, even if he did have the disconcerting habit of "laughing before he got to the punch line".

Off the dance floor and outside the classroom, Gord, a strong swimmer, went out for water polo at DCI, playing at both the junior and senior levels, principally in goal. He ventured into rugby as well. In 1936 he was a gratified member of the championship junior squad and was singled out for his solid play in a season that saw "Delta's hearty boys" defeated only once. This committed athlete also tried his hand at acting - perhaps with his sister's encouragement - and played at least one stage role, that of a servant in the Dramatic Society's production pf Twelfth Night. The following year his full integration into the school was marked by a ritualistic lampooning in the student yearbook, the Lampadion. "Gord Sloane", it gleefully announced in the column "Room News", "is learning to play the bagpipes. It is a well known fact that three canaries in his home have passed away in as many months and that his dog has had the distemper five times", presumably because of the pipes' raucous cacophony. Actually the dog's reaction, as a brother recalled, was to "put his nose up in the air and howl … quite a combination, the howling and the bagpipes". In any case, it was fitting that Gord should join the pipe band of a local Scottish militia regiment, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, and later serve in the unit when it was mobilized for active service overseas.

As expected Gord had little difficulty making the academic adjustment at DCI, and graduated on schedule with his senior matriculation in 1938. McMaster was his first stop after high school just as it had been his sister Jeannette's the year before. She had opted for an English program but her brother registered in the one-year pre-engineering course with a view to completing his studies in mining engineering at Queen's University in Kingston. At that time McMaster had no full-fledged engineering program of its own but did have a "treaty" with Queen's whereby its qualifying students would be admitted to the second year of the latter's Faculty of Applied Science. The McMaster work load was heavy so Gord had comparatively little time for extracurricular activities apart from joining the swimming team. He satisfactorily finished the year with a mixture of seconds and thirds and in September 1939 was duly admitted to the Queen's program. In the intervening summer months he heralded his career plans by taking employment in a mining firm up north, suitably called Northern Empire. He obviously took to it for he did the same the following season.

The close of the 1939 summer proved a momentous time in the life of the country. Only days before Gord took up residence in a Kingston boarding house, Canada had declared war on Germany, following the lead of the United Kingdom and France. For a time Gord entered into the normal round of university activities, that is, whenever his demanding metallurgical engineering studies permitted. Thus he predictably joined the Queen's Pipe Band and, as he had at high school and McMaster, became a valued member of the school's water polo team. Following the passage of the National Resources Mobilization Act in the summer of 1940, Gord, like other male students, was also required to serve in the Queen's Contingent of the Canadian Officers' Training Corps (COTC). He would readily have done so anyway, given his growing concerns about the need for Canada to train qualified officers for eventual military service.

Indeed by the fall of 1940 his thoughts were already turning to the prospect of making a direct contribution to the war effort himself. That sentiment hardened into resolution in the early weeks of 1941. He first mentioned the possibility of enlisting in a conversation in his father's office. Subsequently the senior Sloane pursued the point in a letter he sent Gord in late February 1941. He would have preferred his son to stay with his studies and the COTC until graduation so that if he still wished to enlist, he could be taken on as a qualified engineering officer. Yet he wisely conceded that Gord "must be left free to make [his] own choice", and went on to assure him that "I should be proud … make no mistake about it … to have a son on active service". Gord replied with an equally thoughtful message:

… I have read your letter and I still want to join the army. You have given up a lot to give me a good education but I felt sure that you would sacrifice these efforts if I saw fit to join the army …. I decided that my career … must take second place to what I can do to help win the war …. This war is the biggest thing that ever was inflicted on this earth and I want to be in it no matter how small a part I play…. [Therefore] I find it hard to settle down to my studies and to spend another year [at Queen's] at a time like this would be unbearable.

His understanding father readily gave his blessing, pleased at least that Gord planned to finish his year at the university and take a summer position with the open hearth operation at the Steel Company of Canada, a major industrial plant in Hamilton.

At the same time, however, Gord was determined to enlist and did so as a private in the 2nd (Reserve) Battalion of the aforementioned Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. By November 1941 he had been promoted corporal and the following month, on the basis of his COTC training and educational credentials, he was recommended for a commission. It was conferred on 12 January 1942 on "the strength" -- to quote the assessment of his commanding officer, "of his good character", keenness, and demonstrated "ability to lead". Then unaccountably the newly promoted 2nd lieutenant appears to have fallen through the cracks of the military bureaucracy for not until the following June was he cleared to enlist for active service. Perhaps his "B" medical classification, reflecting some vision problems, may have been responsible for the uncertainty but that seems odd given that he passed muster as a student flyer and was granted his private pilot's license in April 1942. Frustrated and still very eager to do his bit, he may have been contemplating the air force if the army was so reluctant to take him on. In any case, after higher-ups in the political and military worlds intervened on his behalf - perhaps at the urging of his father - Gord was properly inducted into the active army on 5 June 1942. Ironically he could have finished his third year at Queen's and graduated after all. A few days after his formal enlistment Gord was dispatched to the Officers' Training Course (OTC) at Brockville, a place that would become familiar to other McMaster graduates and students seeking to qualify as junior army officers.

After that, things moved reasonably smoothly. In early September 1942, Gord successfully completed the course at Brockville and qualified for the rank of 2nd Lieutenant, Infantry, Active Army. He was deemed "sober and industrious, sensible and rational" though considered "easy going" and therefore needing more experience at being "forceful" as a leader. It was then on to Camp Borden and another training course out of which, on 10 October 1942, he emerged a freshly commissioned 1st lieutenant. Before the year was out he and 18 other ranks were Jamaica-bound to join the 1st Battalion of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

The Argylls had arrived on the Caribbean island in September 1941 and were engaged primarily in garrison and guard duty, their principal responsibility a large internment camp housing captured German merchant seamen and other enemy aliens. For a short time this seemingly unproductive task prompted some of the newly arrived Argylls to look down on their hosts as being less well trained than they. In turn the "original" Argylls regarded the new arrivals as so many "johnnies-come-lately" who failed to appreciate the guardianship role the battalion had been playing. But this would pass as the newcomers became fully integrated into the parent unit. Over the next several months Gord and his newly acquired officer-colleagues kept their men as fully occupied as possible and to that end conducted various training exercises and strenuous route marches, sometimes around the circumference of the island. These were seen as both a toughening-up exercise and an opportunity to "show the flag".

Eventually, the Argylls' "Sojourn in the Sun" came to an end. In May 1943, the regiment was ordered home to Canada. Gord, along with nine hundred other officers and men, together with their equipment, boarded the small troopship S.S. Cuba in Kingston harbour and on the 20th of the month set sail for New Orleans, Louisiana. The passage through the Gulf of Mexico lay through a so-called danger zone known to be haunted by German U-boats. Consequently there were several alerts and at least once the Cuba was the intended target of a torpedo. Fortunately for all on board, the ship successfully zigzagged its way out of danger and Gord and the others arrived safely at their destination. Once disembarked at New Orleans, the Argylls and their effects were speedily transferred to waiting CPR trains and before long were on their way to Canada. For many on board, the Jamaica experience was soon being perceived as a "cohesive force" for the regiment.

On 25 May 1943, Gord and other local soldiers, after a lengthy journey through the States, alighted at Hamilton and were soon reunited with families and friends. The trains continued on to the camp at Niagara-on-the Lake where the regiment would soon be reassembled and given new orders. An unnerving and "sad" weeding-out process was also carried out, affecting those considered too old or otherwise unsuitable for active service overseas. "It was a heart-breaking time", recalled one of Gord's fellow officers, " to know that they [various officers and non-commissioned officers who had helped to provide the regiment's "cohesive force"] were not going to go with us [to England]". Gord may have been dismayed too but he was also relieved to learn that he himself had survived the cut. He had satisfied his superiors that though "shy and quiet" he was nonetheless a "good disciplinarian who should develop with more experience".

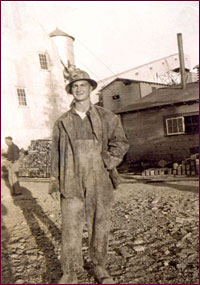

After waiting several weeks at Niagara, in a summer heat probably reminiscent of Jamaica, the reconstituted regiment finally departed for its next stop, Sussex Camp in New Brunswick. A few days after the Argylls' arrival by rail on 11 July 1943, Gord's parents received word of his new circumstances. Among other things, he provided a lengthy description of St. John and the camp's immediate surroundings. He went on to report that one night in the mess he had caught Noel Coward's stirring wartime film "In Which We Serve", one of the many propaganda-heavy items churned out at this time. He was also bemused by the nature of their departure from Niagara. [Though] supposed to be so secret", he told the Sloanes, "it was quite a public affair; there were even people waiting in Union Station as we passed thru [sic] Toronto".

A short week after this letter was written Gord and the Argylls found themselves at dockside in Halifax, Nova Scotia. There they were greeted with the majestic Queen Elizabeth, the erstwhile luxury liner that was about to take them to their next destination, the United Kingdom. It would travel unescorted because it could outpace any U-boat the Germans could put to sea. On 23 July, laden with the Argylls and some twenty thousand other servicemen, the ship set sail and after what its uniformed passengers must have regarded as an amazingly brief four-day voyage, entered the Firth of Clyde and docked at Greenock, near Glasgow. The following day, 28 July, the Argylls disembarked and were put aboard trains heading south to their first overseas training grounds at Camberley, Surrey, less than an hour's drive from London. There the unit's serious training began, a prelude to the regimen it would undergo in preparation - or so it was hoped -- for what would ultimately unfold in Normandy after D-Day, 1944. It was barely a year away.

After Camberley the regiment moved off in September 1943 to the Norfolk coast for more training. For part of that time Gord was engaged in what appear to be weaponry courses at Clacton-on-Sea in Essex. In October, in cold rainy weather - a far cry from Jamaica - he was back with the regiment, participating in a division-level exercise. It was ruefully remembered as the "most exhausting and exasperating period" the unit ever spent in the field with their parent, the 4th Armoured Division. Nor was morale boosted by rumours, later mercifully put to rest, that the Argylls, like some other recently arrived units, might be parcelled out as reinforcements for others. In November the regiment, still very much intact, was again uprooted and on the move to what would become its English home base in Uckfield, Sussex. As was the custom with Canadian forces stationed in England, a Christmas party was held for local children, with the soldiers supplying the treats out of their parcels from home. This was followed by a "great feast" for the Argyll rank and file served by Gord and fellow officers. Then it was back to the military routine. Early in the New Year, Gord was pleased when the rifle team he coached twice won the divisional championship, a picture of the happy squad later appearing in Black Yesterdays, the regimental history. At about the same time, because of his skill and training, Gord was named the regiment's weapons officer.

Not long after this, in February 1944, the Argylls left for Inverary, Scotland where in unusually fine weather they took part in simulated beach landings and combined operations, clearly a signal that something like a cross-Channel invasion was in the cards. Another signal were the regular visits of dignitaries and military "brass", including no less a dignitary than King George VI himself as well as the recently appointed Allied Commander-in-Chief, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Clearly, in view of such august visitations and inspections, not to mention even more intensified training exercises, significant events were in the offing.

Before they unfolded, however, Gord enjoyed a diversion from the rigorous schedule. For a week in April 1944 he was attached to the Royal Navy at the bomb-battered port of Plymouth in the West Country. The appropriate recipient of one of his letters was his brother, Donald, who had recently enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy. Gord told of visits he had paid a British submarine, a gunnery and seamanship school, and finally a Canadian destroyer whose crew and officers had welcomed him with open arms. He also recounted a Channel trip he had made in an escort vessel, all in all a fitting end to his sojourn with the senior service. Later the following month Donald received another letter. It informed him, among other things, that Gord had been taking out an English girl, Jean Williams, and had recently seen her "on a very good weekend in London". They met as regularly as his duties permitted, dining at scenic hotels, seeing shows, or playing tennis. A photograph of the happy pair, presumably taken at Jean's home, has been carefully preserved in a Sloane family album.

Before they unfolded, however, Gord enjoyed a diversion from the rigorous schedule. For a week in April 1944 he was attached to the Royal Navy at the bomb-battered port of Plymouth in the West Country. The appropriate recipient of one of his letters was his brother, Donald, who had recently enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy. Gord told of visits he had paid a British submarine, a gunnery and seamanship school, and finally a Canadian destroyer whose crew and officers had welcomed him with open arms. He also recounted a Channel trip he had made in an escort vessel, all in all a fitting end to his sojourn with the senior service. Later the following month Donald received another letter. It informed him, among other things, that Gord had been taking out an English girl, Jean Williams, and had recently seen her "on a very good weekend in London". They met as regularly as his duties permitted, dining at scenic hotels, seeing shows, or playing tennis. A photograph of the happy pair, presumably taken at Jean's home, has been carefully preserved in a Sloane family album.

By this time, the closing days of May 1944, D-Day was just around the corner. The Argylls, however, were not scheduled to be in the landing forces on 6 June 1944, their departure set for a later date. "After [thus] waiting on our fannies for something to happen" - to quote one of Gord's letters - the Argylls' own D-Day finally came, according to one account, on 20 July 1944 when they went aboard an American Liberty ship on the Thames for the journey across the Channel. After a weather-dictated delay they arrived on 25 July at Courcelles, Normandy, in the Canadian sector known as Juno Beach. (On the other hand, Gord's service record states that he left England on 19 July and disembarked in France two days later.) On the ship's way through the Channel - after braving the German guns at Calais -- Gord told of sighting enemy "buzz bombs" (pilotless V-1 rockets) and the dramatic downing of an unidentified fighter. When they finally disembarked he experienced the "thrill" of landing "on the beaches that had been fought over not so long ago".

The Argylls did not stay on the beaches for long, quickly moving inland and camping at a spot northwest of Caen, the strategic road and rail centre captured by the Canadians earlier in the month. The camp was thankfully located near a river, which, Gord told Jeannette, provided them with a welcome opportunity for a "swim and a wash". The Normandy countryside round about them has been described by brother Douglas as a "landscape … bare … and treeless … an area of windswept fields, dotted with villages … its fertility … encourag[ing] large scale farming, but its dryness preclud[ing] pasturage …." Briefly ensconced in these new surroundings, Gord hastened to assure Jeannette and the family that the regiment was still "a good way from the front".

That situation would soon change dramatically. In short order the Argylls were subjected to the harsh sights, sounds, and smells of war as they moved up to the front through the shattered remains of Buron and Caen. This was the heart of the post-D-Day killing fields that had already claimed the lives of McMaster alumni Robert Dorsey [HR] and Nairn Boyd [HR]. "That was our real initiation" recalled a former Argyll rifleman, " …That's where I saw the first mass grave … where a bulldozer … scooped out a big long ditch and then they started bringing in the bodies…. [T]he whole area smelled ... from the people ... and the cattle killed …." On 29 July the regiment suffered its own casualties, its first; "the fortunes of war", an Argyll sergeant philosophically recalled, "somebody got it". The next day the unit was in the front line itself, the day after that - 31 July -- it was in Bourguebus, a village south-east of Caen, and on its way to Tilly-la-Campagne and ultimately, it was hoped, Falaise.

Tilly, a once picturesque place of traditional Norman fieldstone, was proving to be another killing field in the making, already the scene of fierce fighting between comparatively green Canadian troops and battle-hardened and resourceful Germans. The enemy was endeavouring with all the formidable means at his disposal to thwart an Allied attempt to close the so-called Falaise gap through which the partially entrapped German 7th Army was seeking to escape. To that end the foe had turned every village and hamlet, including Tilly, into a defiant mini-fortress. The Canadians were called upon to organize an attack specifically on Tilly because it occupied high ground that conferred key advantages upon the enemy and effectively dominated the crucial Caen-Falaise highway.

Before the Argylls appeared on the scene, such units as the North Nova Scotia Highlanders, in an operation dubbed "Spring", had launched attacks on the village. But they had been ill directed and poorly organized and as a result had been repulsed with heavy losses. Moreover, the Nova Scotians had suffered further heavy casualties when they were counterattacked by the 1st Panzer Korps. The enemy, in effect, had won a significant "defensive victory" and turned Spring, in the words of a Canadian military historian, "into a disaster of major proportions". It prompted a board of enquiry, and subsequently several senior officers were relieved of their commands. The episode indeed was apparently symptomatic of problems that had plagued the Canadian high command from the very beginning. Recently historians have noted that it often failed to exploit opportunities to entrap or dislodge the enemy. Further, unlike the Germans, those in charge of the campaign had invariably acted "ponderously" and unimaginatively, so much so that front line Canadian troop had often suffered needless losses.

In these distressing circumstances, understandably better co-ordinated attacks were undertaken. But despite the best efforts of such units as the Calgary Highlanders and the Lincoln and Welland Regiment, a determined and inventive foe held them at bay. Eventually it was the Argylls' turn, as part of the 4th Armoured Division, to mount an attack. Moving forward from Bourguebus in the late afternoon of 5 August, the regiment deployed before a deceptively quiet Tilly and sent out a platoon to reconnoitre the village. Suddenly the place came alive and the platoon, like so many units before it, was pinned down by heavy enemy fire and shortly withdrawn, though not before taking several German prisoners. Orders were then given for a concerted infantry and armoured assault on the village. In all, some one hundred and eighty men, drawn from the Argylls' "C" and "D" Companies, would be involved along with "C" Squadron of the South Alberta (Tank) Regiment (SAR). Lieutenant Gordon Sloane, commander of one of "C" Company's platoons, was about to join the action.

In the early evening of 5 August 1944, Gord's platoon, the leading one, accompanied by the SAR's Sherman tanks, advanced straight into Tilly. It was instantly met by ferocious fire from elements of the 1st SS Panzer Division. High velocity 88s, the prize enemy artillery, made short work of most of the Shermans while machine gun and mortar fire soon decimated Gord's platoon and struck down its commander. Indeed, so impenetrable was the German defense that the decision was shortly made to withdraw the entire force. According to a report prepared a month later, one based on eye-witness accounts, Gord,

"contrary to divisional orders, was right up front with his lead section. He went through that terrible fire to within hand grenade distance of the enemy. This was a magnificent bit of work … the men of his platoon [who] … talk of him as their best officer … state that he was killed attacking a machine gun post [or 88 gun emplacement] with hand grenades. No officer to this date has carried himself through danger like Gordon did, as far as I know, in this battalion.

The battalion adjutant, a McMaster graduate, who had relayed orders to Gord just hours before his death, confirmed the judgment. Nearly a half century later Donald Seldon was still extolling "platoon commanders like Gord who were right in the thick of the fighting".

Though Gord was initially reported missing his teenage brother Douglas overheard sister Jeannette remark that "I know he is gone because he is too proud to have been captured". She was right. On 25 August 1944 her brother was taken off the missing list and officially declared killed in action. Regrettably Gord did not live to see the capture of what remained of stricken Tilly-la-Campagne, which occurred three days after his death when it was finally liberated by the tanks of the British 154th Brigade. Then two weeks later the Falaise gap itself was closed off, thus bringing an end to the bloody battle of Normandy. To that battle Lieutenant Gordon Sloane had made his own signal contribution.

James Gordon Sloane is buried in Bretteville-sur-Laize Canadian War Cemetery, Calvados, France.

C.M. Johnston

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: First and foremost, Douglas Sloane's exemplary biographical account of his brother, Gordon, is singled out for special mention. His well documented "Lieutenant James Gordon Sloane and the Battle for Tilly-la-Campagne", clearly a labour of love, has been extensively quarried for this Honour Roll piece. The manuscript's author painstakingly prepared it in the months leading up to his death some years ago.

Others who kindly helped included Jeannette (Sloane) Parsons, Kelly Sloane, Patricia Sloane, Michael Sloane, and Mark Steinacher. All in their varied and important ways contributed to the making of this biography, whether it was furnishing leads, recollections, and documentation or providing archival and editorial assistance. Patricia and Michael Sloane produced Douglas Sloane's historical accounts, family photograph albums, and other documentation.

SOURCES: National Archives of Canada: Wartime Personnel Records / Service Record of Lieutenant James Gordon Sloane; Commonwealth War Graves Commission: Commemorative Information, Lieut. James Gordon Sloane; R. Douglas Sloane, "Lieutenant James Gordon Sloane and the Battle for Tilly-la-Campagne, August 1944" [with Appendix: War Diary of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, 1 Jul. 44 - 5 Aug. 44] (Etobicoke ON: 1994), especially 9-32 (manuscript in the possession of the Sloane family); Robert L. Fraser, Black Yesterdays: The Argylls' War (Hamilton ON: Argyll Regimental Foundation, 1996), 41, 123, 141, 143, 147,167, 175, 185, 196, 206, 207, 208, 213, 217-18, 537, 539, 547-8; Terry Copp and Robert Vogel, The Maple Leaf Route: Falaise (Alma ON: Maple Leaf Route, 1983), 66-70; Internet: Roman Johann Jarymowycz, German Counter-Attacks during Operation Spring, 25-26 July 1944, www.wlu.ca/…www.msds/vol2n/opspringjarymowycz; Denis Whitaker and Sheilagh Whitaker with Terry Copp, Victory at Falaise: The Soldiers' Story (HarperCollins, 2000), 115-16; John A. English, The Canadian Army in the Normandy Campaign: A Study of Failure in High Command (New York: Praeger, 1991); C.P. Stacey, Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, III: The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe, 1944-1945 (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1960), 186-93, 204-8; John Morgan Gray, Fun Tomorrow: Learning to be a Publisher and Much Else (Toronto: Macmillan, 1978), 272.

Delta Secondary School Library: Lampadion, 1936, [28], 1937, 21, 24, [37], 57, 1938, 44, 69, 88; Delta Alumni Society Archives: Snell Scrapbooks, the 1930s (DCI Dramatic Society Programmes); Canadian Baptist Archives / McMaster Divinity College: McMaster Student File 6902, J. Gordon Sloane, Biographical File, J. Gordon Sloane; McMaster University Library / W. Ready Archives: Marmor, 1938-39, 108, 1939, 42, McMaster Alumni News, 12 Oct. 1944.

[ For related biographies, see Kenner Sawle Arrell , Gordon Rosebrugh Holder , William Allen McKeon ]