Dr. C.M. Johnston's Project

Discover McMaster's World War II Honour Roll

Francis J. Jensen

Hamiltonian Francis (Frank) Jensen, like his Catholic co–religionist, Hank Novak [HR], came out of the heart of the city’s vibrantly multiethnic Northeast End. He was born in the midst of the First World War, on 8 November 1917, the second son of a Danish immigrant who became a naturalized Canadian citizen, and Canadian-born Catharine O’Meara. Frank joined an older brother Vincent, who entered the priesthood, and would be followed in turn by a sister, Anne, the future Mrs. William Ferris. The family, which resided at 138 Rosslyn Avenue North, worshipped at St. Anne’s Church and the children were educated at the affiliated separate school that bore the same name.

Hamiltonian Francis (Frank) Jensen, like his Catholic co–religionist, Hank Novak [HR], came out of the heart of the city’s vibrantly multiethnic Northeast End. He was born in the midst of the First World War, on 8 November 1917, the second son of a Danish immigrant who became a naturalized Canadian citizen, and Canadian-born Catharine O’Meara. Frank joined an older brother Vincent, who entered the priesthood, and would be followed in turn by a sister, Anne, the future Mrs. William Ferris. The family, which resided at 138 Rosslyn Avenue North, worshipped at St. Anne’s Church and the children were educated at the affiliated separate school that bore the same name.

In September 1929, after completing his primary schooling at St. Anne’s, Frank enrolled at Cathedral High School (originally Catholic High School) the city’s only separate secondary institution for boys. He did well academically at Cathedral and in his final year was the winner of the Bishop McNally Gold Medal in General Proficiency, an honour recorded in the Hamilton Spectator on 7 December 1934. He also made a distinctive mark in public speaking and debating, for which Cathedral enjoyed a considerable reputation. With an eye to his possible post–secondary future at university, he applied for and won a Knights of Columbus Scholarship.

Armed with this aid and his family’s support, the hopeful undergraduate–to–be, at the comparatively tender age of sixteen, showed up on McMaster University’s doorstep in September 1934. Having received his bishop’s permission to do so, he applied for admission to this Baptist institution, which had just four years before re–located from Toronto to its new home in Westdale. The upshot was that on 18 September Frank was duly registered in Honour Mathematics and Physics, his chosen areas of study.

At the end of his second year in the course, which he cleared, he sought on 15 March 1936 to change his academic menu, finding physics not as appetizing as he had hoped. The administration saw it his way, allowing him to drop Physics for Economics, understandably a popular subject for those students trying to make sense out of the precedent–setting Depression of the ‘thirties. Frank may well have shared this urge but his request for a switch in subjects was, as he told the administration, dictated specifically by a desire to pursue an actuarial career.

On another occasion the higher–ups were not so malleable when Frank submitted a request, this one inspired by his Catholicism. With respect to a French elective he was taking, he petitioned to be excused from studying some controversial literary texts banned by the Vatican. “The matter has not arisen before”, wrote a bemused Professor Kenneth Taylor, the Dean of Arts, in a memo to colleagues. “This may be a case of an oversensitive conscience or it may be a test case. After a full discussion it was decided not to grant the petition”.

While coping as best he could with problematic French texts, Frank continued to ponder the intricacies of economics. He also ventured into the world of the extracurricular, throwing himself into what he had enjoyed and excelled in at Cathedral, public speaking and debating. Clearly he had lost none of his skills, winning in his third year a gold medal in an oratorical contest. The same success marked his debating efforts, as noted in the Silhouette, the student weekly, which extensively covered McMaster’s participation in the Inter–Varsity Debating League. In every debate, the weekly exulted, Frank and his team mates “upheld McMaster’s proud tradition” in this extracurricular verbal jousting.

Some of the well attended debates reflected the worsening political situation in Europe where dictators Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Joseph Stalin were threatening the peace so dearly bought in the First World War, just twenty years before. Visiting speakers with varying degrees of expertise descended on campus to tell the International Relations Club and other interested student groups not only of the looming danger overseas but of the hitherto unthinkable, the inevitability of another world war. Frank and many of his classmates were soon caught up in the discussion.

Either out of conviction or a sense of challenge – or both – Frank in one debate took the negative side on: “Resolved that Canada should Prohibit by law the preaching of Communism and Fascism”. According to an impressed Silhouette, Frank ably made the case for his side, arguing that at a time of economic meltdown and massive joblessness, “Suppression will not stamp out Communism or Fascism ... as long as there is inequality those who have not will demand justice from those who have and suppression merely breeds vigour.”

His use of “haves” and “havenots” deployed a catchphrase that would dominate the rest of the century and beyond whenever social and economic ills dominated the conversation.

Frank’s success as a debater was also duly recorded in the Marmor, the student yearbook. “Shortly after the opening of the fall term [in 1937]”, a yearbook staffer wrote, “two Mac men, Frank Jensen and Frank Stevens, met and defeated a team from the Maritimes in the prestigious Annual National Federation of Canadian University Students (NFCUS) debate.” The resolution for the occasion was: “That the sit–down strike is a just organ in the hands of organized labour”. Like the ideological debate on Europe, this one opened a window to the problems of the Depression ‘thirties, the labour strife that erupted up and down the country. Again Frank’s own way of thinking may have made it to the surface. On another occasion he and his team enjoyed a trip to Montreal where he led it to a win over Loyola College.

Frank also found time to dabble in campus journalism, working periodically as a sports reporter for the Silhouette. He rounded off his extracurricular program by serving as studies–related treasurer of the Newman Club, a Catholic student counterpart to the Christian Union that had long flourished on campus. The friend who composed Frank’s Marmor “obit”, which summarized his accomplishments when he graduated in 1938, ended with a question that probably reflected the mood of those troubled and uncertain times: “The Future – who knows?” Even so, for his immediate future Frank had briefly contemplated a master’s degree in economics at his alma mater. Though accepted, he eventually chose to ignore “repeated requests” to show up for the necessary appointments and paperwork.

Thus it was on to the workplace instead and a possible career as an actuary. But apparently he had to settle for a variety of general office jobs until December 1943, when he landed a position as a cost accountant with the Cub Aircraft Company located at the Hamilton Airport, close by the community of Mount Hope. By this time the Second World War was in its fourth punishing year and the Airport had long been serving the needs of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, an Anglo–Canadian arrangement set up in 1939 to provide trained aircrew for combat overseas. The Western Allied ground war in Europe, hitherto confined to Italy, was also about to take a highly dramatic turn. On 6 June 1944 American, British, and Canadian forces took part in the long awaited D–day operation, the cross–Channel invasion of Normandy. For weeks it would be fully covered on the front pages of the Hamilton Spectator.

Perhaps these galvanizing events helped to decide Frank’s immediate future. He decided to swap cost accounting for soldiering and on 23 June 1944 he travelled to Toronto and enlisted for active service with the Canadian Army. Unlike some others he did so as a raw recruit, having had no previous military experience in, say, a local militia battalion or part–time military training corps. Nor for some reason had he been conscripted under the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA), which limited service to North America, a concession to Quebec, which traditionally opposed compulsory service overseas.

In any case, Frank was soon decked out in khaki battledress and given an official serial number to boot – B–162564. Four days after he joined up he was granted a 6–day enlistment leave presumably spent with family and friends in Hamilton. Meanwhile he had been posted to an infantry training camp in Brantford where he was introduced to military drill and given his basic training. While there in mid–August he fell ill from an unnamed ailment and was hospitalized for five days. On his last night there, he created a stir by going AWOL (Absent Without Leave) and not returning until dawn broke eight hours later. Where he went and what he did in that interval is unknown. For his pains the runaway patient was docked a day’s pay, which at this time amounted to $1.40.

On 16 September1944 the partially trained Frank left Brantford for Camp Borden, still the country’s premier military station, where he would receive more intensive training before being dispatched to the battle front. Toward the end of his stay at Camp Borden he was told that he did not qualify as a tradesman, which may have cost him a stripe or two. Obviously his debating skills and university degree cut little or no ice with a military on the lookout for other talents and credentials in those recruited to offset the worrying Canadian losses on the battlefield. At any rate, in November a sign that Frank would soon be on the move to Britain came in the form of a special 3–day leave followed by an even more welcome fourteen–day furlough, which was tantamount to an embarkation leave. On December 10th, a week after it expired, Frank was on his way to a training and marshalling centre at Debert, Nova Scotia, the penultimate stop before boarding ship in Halifax.

That day duly came on December 18th when Frank and hundreds of other servicemen went aboard their troopship and set sail for a UK destination. The passage was seemingly uneventful save for the Christmas celebrations on shipboard, which bravely tried to match the traditional festivities in Canada. Two days after Christmas Frank and the other military passengers disembarked at an unnamed British port. Frank reported for duty the next day and may also have sent the customary cable home announcing his safe arrival. He was subsequently ordered to a training camp in southern England where, besides fine–tuning his training, he and others were lectured by war–seasoned veterans on what lay ahead, the nature, the extent, the cost, and the objectives of the fighting raging in Holland. For Frank and his fellow uninitiated it must have been an intimidating indoctrination, even if leavened by some necessary morale–boosting talk as well.

On February 14th Frank was alerted to his impending trip to the Continent. He was given a short embarkation leave, shared unexpectedly with an old Cathedral friend, Lieutenant Thomas Sturrock. On the 17th they and other reinforcements were flown in an air transport, likely a workhorse Dakota C–47, to what Frank’s service record simply called “north–west Europe”, quite possibly an airfield in liberated Belgium. Though the two friends were assigned to the same Canadian brigade they would fight in different regiments. After still more preparation over the next few days Frank for his part was finally assigned on February 23rd to the 1stBattalion of the Royal Regiment of Canada (Royals), his last posting. He was among the many green and untried, not to mention apprehensive soldiers being fed into the battle–thinned ranks of front line regiments that made up parts of the 1st Canadian Army. This was the first sizeable reinforcement that it had received for some time.

The ancestor of the Royals, a venerable unit by Canadian standards, had made its appearance in 1862 during the troubling times of the American Civil War. The regiment helped to fend off the postwar Fenian Raids and later to quell the Northwest Rebellion. It also served in the South African War and the far more horrific world wars of the twentieth century. In the second of those conflicts the Royals, alongside other Canadian units, had fought through Normandy, northeastern France, Belgium, and southern Holland. By the time the novice Frank Jensen, joined them, the Royals and their sister units, among them, the Essex Scottish, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry (RHLI), and the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, were fighting for the first time on German soil, in the so–called Battle of the Rhineland. These combined units made up the 4thBrigade of the 2nd Canadian Division, which together with four comrade divisions comprised the 1st Canadian Army. Each division was responsible for a comparatively narrow sector of the Rhineland front.

After receiving much needed advice and encouragement from battle–tried survivors, Frank was soon initiated into the harrowing regimen of a front line almost constantly subjected to the ear–splitting sounds, gut–wrenching sights, and sickening stench of battle. The appalling effects of the “Fascism” he had airily debated as an innocent undergraduate were now staring him straight in the face. But amidst the carnage life of sorts went on. Sometimes in the chaos of the fighting, hot food did not make it to the Canadians, who moreover were often obliged to take shelter in hastily dug slit trenches, a situation made worse by frequent soggy winter weather that eroded the trenches and turned what passed for roads into tank–entrapping quagmires.

When the rains stopped and the sun did shine, however, the mud dried up, freeing the armour and allowing RAF aircraft, including cannon–firing Typhoons, to resume their harassment of enemy defenders and to strike targets across the Rhine. Though there were welcome but all too rare lulls in the fighting in which units could rest, reorganize, and refit, there was always combat looming just around the corner. Throughout the campaign the beleaguered Germans, fighting with their backs to the wall and on their own native ground, reacted fiercely with everything in their formidable arsenal. “The fighting”, one Canadian combat office observed, “was almost as severe as ‘Normandy’.”

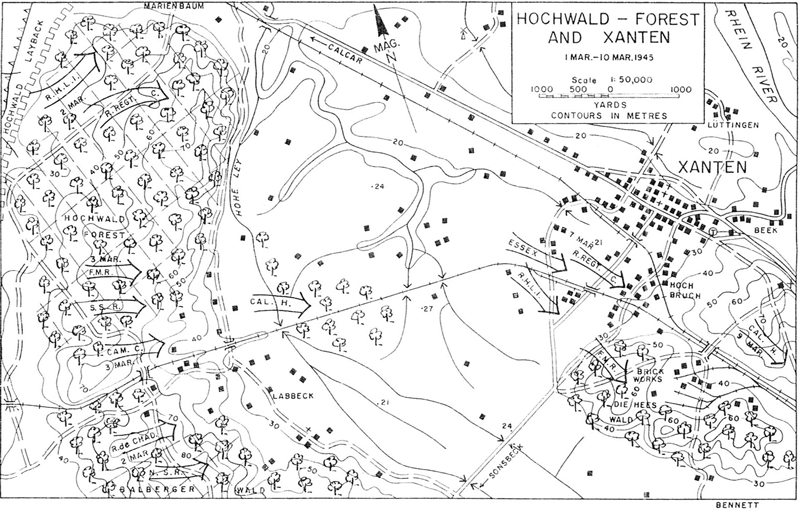

All these factors characterized a major Canadian offensive dubbed Blockbuster, which was launched in the closing days of February. It was designed to accelerate the by now heavily reinforced Canadian offensive, an integral accompaniment to an Anglo–American push to eliminate once and for all the stiff enemy resistance west of the Rhine. The Canadians’ first and vital chore was to drive the Germans out of the Hochwald, a thick and lengthy German state forest that dominated the Canadians’ line of advance (see full-sized map). In the main good progress was made by the hard–driving Royals and the rest of the brigade. Meanwhile drier weather elsewhere on the Rhine helped the Anglo–Canadian cause by clearing up the worst of the flooding in the Ruhr Valley, which had temporarily bogged down the American contribution to the operation.

All these factors characterized a major Canadian offensive dubbed Blockbuster, which was launched in the closing days of February. It was designed to accelerate the by now heavily reinforced Canadian offensive, an integral accompaniment to an Anglo–American push to eliminate once and for all the stiff enemy resistance west of the Rhine. The Canadians’ first and vital chore was to drive the Germans out of the Hochwald, a thick and lengthy German state forest that dominated the Canadians’ line of advance (see full-sized map). In the main good progress was made by the hard–driving Royals and the rest of the brigade. Meanwhile drier weather elsewhere on the Rhine helped the Anglo–Canadian cause by clearing up the worst of the flooding in the Ruhr Valley, which had temporarily bogged down the American contribution to the operation.

The good fortune that attended the Royals’ efforts was denied the nearby 10thBrigade of the 3rd Canadian Division to break out through the Hochwald Gap separating the Hochwald from the Balbergerwald. Apart from this temporary tactical reverse the 1st Canadian Army by the opening days of March had made considerable progress. At the battalion level, the Royals for their part were ordered to clear the northwest edge of the Hochwald and began their attack at dawn on March 3rd. The regimental war diary recorded that day’s events:

AM dawned cold and overcast–

The weather today was cool and wet occasional rain and snow.

Battle proceeded according to plan. All coys [companies] were consolidated on their objectives by 1000 hrs [hours].

Resistance was not as stiff as expected but, after consolidation, the mortar and shellfire was very heavy and comparable to that of “Normandy” days.

Well –sited enemy [machine guns] constituted the only real obstacle to our advance.

South–east and north of our posn [position] was then thoroughly cleared....

Casualties today were – [one lieutenant] wounded and 12 ORs [other ranks] killed, 29 wounded and 1 missing. ...

One of the casualties was Private Frank Jensen. He was mortally wounded in the thorax by flying shrapnel during the heavy shelling noted in the war diary. Another fatality that day was his old Cathedral chum, Lieut. Sturrock, who had been posted to the RHLI. The twenty–seven year old Frank had spent a mere nine calendar days on the front line, but those hectic and hair–raising days probably seemed more like weeks. When it received word of his death, the McMaster Alumni News, as it did on all such occasions, paid him as warm tribute. The day after Frank was killed, the Hochwald operation was judged complete, thus ensuring the successful conclusion of Blockbuster. The way to and over the Rhone into the heart of Nazi Germany was now open to the Royals and the other units making up the 1st Canadian Army. The war in Europe ended a bare two months after Frank died in the Rhineland.

Francis Joseph Jensen is buried in Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery, near Nijmegen, Holland.

C.M. Johnston & Lorna Johnston

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The following provided helpful data and leads: Kenneth Allen (Cathedral High School), Susan Elliott (St. Anne’s Church), Elizabeth Ferris (Wm. Ferris’ granddaughter), Robert Johnston (war memoirs), and Adam McCulloch and Kenneth Morgan (Canadian Baptist Archives). Sheila Turcon (McMaster University Library) did the same.

SOURCES: National Archives of Canada RG 24: Service Record of Private Frank Joseph Jensen, War Diary of 1st Battalion, Royal Regiment of Canada, 23 February to 4 March 1945; Commonwealth War Graves Commission, Commemorative information on Frank Jensen, McMaster Divinity College/ Canadian Baptist Archives: Student File 6229, Frank Jensen, Biographical File, Frank Jensen; Silhouette,14 March 1937, 17, 24, Feb., 2, 10, 17 March, 18 Nov. 1938; Marmor 1937-38 , 23, 66, 67, 77; McMaster Alumni News, 24 March 1945; Hamilton Spectator, 7 Dec. 1934, 14 March 1945; D.C. Goodspeed, Battle Royal: A History of the Royal Regi,ment of Canada, 1862-1962 (Toronto: Royal Regiment of Canada Association,1962), 538-43, C.P. Stacey, Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second Word War, III: The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe, 1944-1945 (Ottawa, Queen’s Printer, 1966 ed.), pp. 491-526.

[ For related battle scenes, see Ruthven Colquhoun McNairn, Section IV. ]