Dr. C.M. Johnston's Project

Discover McMaster's World War II Honour Roll

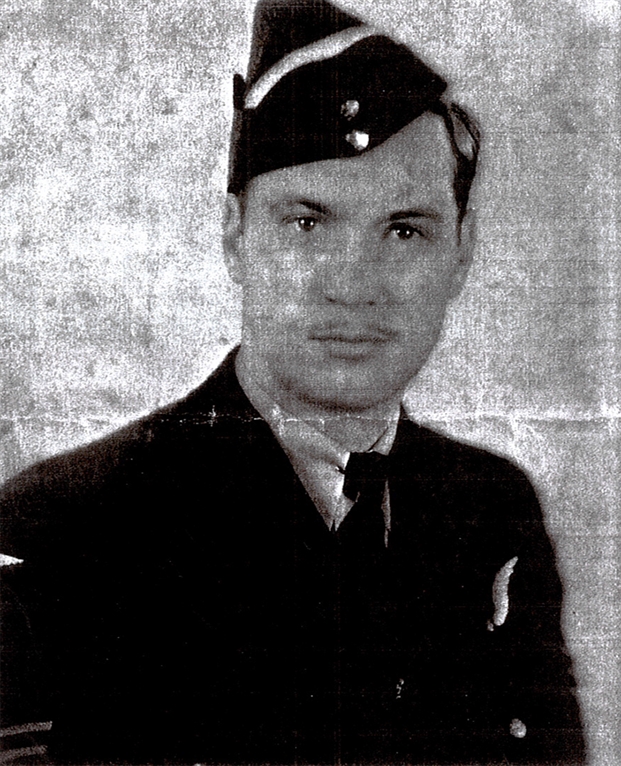

Charles M. Holman

Charles (Chuck) Holman lived two wartime lives and merits a kind of dual biography. He served in different capacities in two Second World War air arms, starting off with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and ending up in the United States Army Air Force (USAAF). In the former he trained as an air gunner. I n the latter he served an entirely different role as a ground crew tradesman. All this flowed from what amounted at times to a dual allegiance.

Charles (Chuck) Holman lived two wartime lives and merits a kind of dual biography. He served in different capacities in two Second World War air arms, starting off with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and ending up in the United States Army Air Force (USAAF). In the former he trained as an air gunner. I n the latter he served an entirely different role as a ground crew tradesman. All this flowed from what amounted at times to a dual allegiance.

His complex and often turbulent life began on 16 April 1916 in the Georgian Bay boat-building town of Collingwood, the home of his mother, Annabelle. There his English-born father, the son of Old Country immigrants residing in Hamilton, Charles Thompson Holman, was temporarily serving the pastoral needs of the local Baptist Church, part of his duties as a theology professor at his alma mater, McMaster University. At that time, McMaster was located in Toronto where he had graduated BA and MA in 1908 and 1909 respectively. Chuck’s mother also gave birth to his older sister, Jane, the future Mrs. H.J. Wharton of Pittsburgh, and his much younger brother, Robert, a resident of Illinois, who supplied valuable recollections of the Holman family.

Shortly before Chuck’s birth, his father established his first connection with the University of Chicago when he reinforced his McMaster training by earning a BD in theology at the institution on Lake Michigan. He subsequently strengthened his academic credentials by studying psychology and philosophy at Indiana University. In 1923 he forged a permanent bond with the University of Chicago when he was appointed as a professor to its Divinity College.

Leaving one Great Lakes community for another, the seven-year old Chuck Holman would grow up in the vibrant as well as crime-stricken Chicago of the Roaring Twenties, dominated by the notorious mobster, Al Capone, who sadly personified for many the Windy City of the Prohibition era. The youngster was likely shielded from much of the seamier side of his surroundings as he progressed under his parent’s watchful eye through Chicago’s school system. Completing his elementary instruction at the Fiske and Parker School, he proceeded to the related Parker High School and while there tasted a bit of adventure and some income by spending three of his summer recesses working as a deckhand and watchman on Great Lakes ore boats. This was a job he might have come by through a maternal uncle who was a shore captain with the Chicago based Patterson Line. His family invariably spent two months each summer in Collingwood where his mother’s family resided.

Chuck’s respectful younger brother, Robert, described him as “generous to a fault, athletic, intelligent and caring”. But he added that Chuck always “wanted to be number one, yet at times [was] very insecure”. Perhaps to keep the insecurity at bay, he had joined the Boy Scouts and predictably rose to become an Eagle Scout and patrol leader. He also added to his laurels by excelling as a sharpshooter with The National Rifle Association. Chuck’s obvious desire to be “number one” quite possibly alienated his older sister, who, according to Robert, came to regard him as a “royal pain the ass”.

After high school, instead of proceeding to an American institution of higher learning, he was dispatched to his father’s alma mater, McMaster University, now relocated on a spacious campus on the western edge of the City of Hamilton. The senior Holman’s decision was probably motivated by a desire to renew his Canadian ties and to ensure that his son would experience the kind of advanced education he had a quarter century before. In any case, Chuck entered McMaster in September 1934 and registered in a mathematics course, after indicating that he wanted to become either a mathematician or a psychiatrist, two disciplines not ordinarily lumped together.

In his first term, however, he fell ill and an appreciative Holman senior wrote Registrar Elven J. Bengough to thank the University for its “kindness” in caring for Chuck during his bout with ill health. Two months later, his father again wrote Bengough about his son’s “disappointing standings” on the January examinations. He went on to say that while Chuck “makes no alibi, I understand that he was not at all well when the exams were written”. He also reported that Chuck had “four times as many white corpuscles in his blood as is normal, together with low blood pressure and low resistance”. These were quite possibly the symptoms of a serious infection for which the critical curatives of penicillin and antibiotics were still in the future.

All the same, whatever medications or care Chuck received did the trick. Bengough could respond a few days later that “I have been quite delighted to see how rapidly Charles got back to regular work and I hope I will find his general condition improving as time goes on so he may be able to make a better showing at the spring examinations”.

Chuck’s rapid recovery may have owed something to his burgeoning love affair with fellow undergraduate Marie Agnes Dunoon. They had much in common. Both were born the same year and raised Baptist. They also hailed from the same Georgian Bay area, and had older male family members who could claim McMaster as their alma mater. At McMaster both lived in close proximity on campus, Marie in Wallingford Hall, the women’s brick tudor residence, and Chuck in Edwards Hall, the men’s equally attractive counterpart. They presumably met and re-met, if not in class, then at least at the supervised inter-hall teas and socials that were then the order of the day. The courtship obviously went into high gear. Before the 1935-6 session ended the two young people decided to get married and withdraw from the University without graduating. During his stay the records show that he took no part in club activities or sports though he took time from his studies to perform as a cheerleader for the football team. In due course, a year later, in late May 1937, the newlyweds’ baby daughter arrived, Georgia Jane (Geo) Holman.

In the meantime the couple had settled in Chicago, where faced with family responsibilities, they sought gainful employment and or continuing education to advance their careers. Chuck, for his part, was fortunate to land a position as manager with a small Chicago Co-operative Union. Marie in turn took the opportunity to continue her interrupted undergraduate studies at the University of Chicago, receiving her AB in December, 1939.

Though occupied with what appeared to be a full-time job, Chuck too was anxious to complete his own disrupted education in one form or another. In early May 1939 he requested the ever helpful Bengough to mail his McMaster transcripts directly to Woodrow Wilson Junior College where he hoped to complete some of his post-secondary education. He apparently gave up employment to enter college so that he might follow in Marie’s footsteps to the University of Chicago. All the same, he still found time to star as a college footballer, a role played by his father at McMaster. In any case the academic strategy of going to Woodrow Wilson seemed to work. In early September 1939 Marie told Bengough that “Chuck was doing excellent work at the University here”. She then requested and duly received her own McMaster transcripts so that she could clinch a position offered at Herzl Junior College in Chicago, where she would serve as secretary to its president. Now firmly ensconced in Chicago, she took the next step, applying for US citizenship, which was conferred on her in September, 1940.

By that date the Second World War was raging full out overseas. Holland, Belgium, and the once formidable France had been speedily overrun by a catastrophic German Blitzkrieg. For its part, an embattled Royal Air Force (RAF) had only very recently eked out a narrow but welcome victory in the so-called Battle of Britain and averted an immediate German invasion of England. In these dire times Marie wrote an interested Bengough that the Americans she knew seemed more agitated by alarming overseas events than more reticent Canadians appeared to be. Be that as it may, her husband was among those Americans “worked up” by the full blown crisis in Europe. Though technically a neutral, he was impelled by his Canadian roots and English heritage to enlist in the fledgling RCAF. As his brother Robert observed, “I don’t believe that Chuck doubted his status as an American, but certainly all of us had a multinational outlook”.

According to his RCAF service record Chuck repaired to Hamilton on 25 June 1940 to seek admission to the RCAF. His interviewing officer was clearly impressed with this six foot well turned out and pleasant recruit, noting above all his education and keen intelligence. He also went on to say that Chuck could be considered aircrew material as either a pilot or navigator at a commissioned rank. Because of the heavy rate of enlistment in that fateful summer of 1940, fully a month passed before Chuck was formally inducted on 22 July at No.1 Manning Depot in Toronto. There for the next three weeks he was put through the disciplined paces of so-called airmanship, which ironically amounted to a good deal of soldiering, including much drilling and marching.

During his time at 2 WS he managed visits to his wife in Chicago. Marie in turn had kept Registrar Bengough up to date on Chuck’s gratifying progress in the RCAF. But on his leave visits to Chicago he had no chance to see daughter Georgia, who had been shipped off to Marie’s parents in Owen Sound, so that she could take up full time employment as a laboratory assistant at a local hospital.

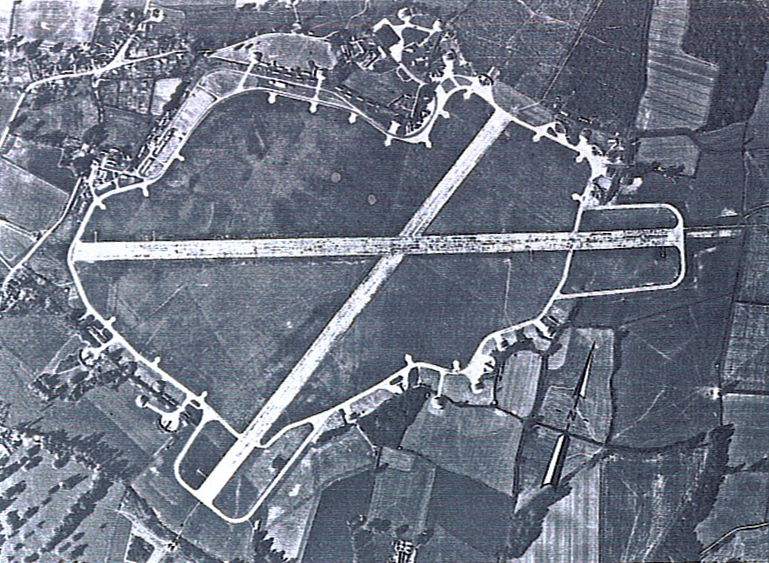

In the meantime, Chuck moved on in mid-February 1941 to a new posting in the province of his birth, specifically to No. 4 Bombing and Gunnery School (BGS) at Fingal in southwestern Ont. Over the course of a month he trained and qualified as an air gunner and as a

result was promoted sergeant and authorized to wear the air gunner badge. On March 16th the newly minted NCO entrained for Debert, Nova Scotia, where he and other military personnel bound for overseas were temporarily accommodated while waiting for a ship out of nearby Halifax.

Clearly shipping was in great demand because apparently their ocean transport to the UK did not materialize until late the following month. On this point his service record is silent, indeed entering a question mark in the space provided for that information.

What is certain is that he arrived in Scotland on 1 May 1941 after what was for Chuck an unhappy stopover in Iceland. Immediately following his arrival, he was whisked off on May 2nd to 3 Personnel Reception Centre (PRC) at Bournemouth on the English Channel, the designated rendezvous for most RCAF arrivals. He wrote a serial letter to his “Dearest” Marie, telling her that it was “great to get somewhere where there are friendly faces. Everyone was waving to the train as we passed. We really felt welcomed. It was double good after Iceland [censored]. We thought that the first glimpse of Scotland from the ship was great – but nothing like getting ashore – really here. I’m going to love it here. I am afraid you will have to bring Geoey here when the war is over: I won’t want to be going back. Mebbe [sic] for a visit only. Most of the women we see here wear slacks everywhere -- because they can’t get silk stockings, I guess. The cotton stockings are ugly – they make the women look like peasants.”

Further on in the letter, Chuck reported: “We are settled in our new quarters and going to town tonight. All this stuff you hear about rations is a lot of hooey. We eat better now than we ever did in Canada. Cigarettes, however, are reserved for H. M. [His Majesty’s] forces, I believe … and civilians have to go without. It’s hard to believe that this is a country at war: very quiet and peaceful out and few damaged buildings. Wreckage is more an oddity than a commonplace”. I have yet to see a Jerry plane.”

He then fulsomely described his sergeant’s quarters “as better than the officers”, reminding this former Edwards Hall resident of “a college dormitory”.

Some days later, he found himself in London, the Imperial metropolis. There he witnessed a scene far removed from his first sanguine impressions of a country, at war, so much so that he sharply revised what he had previously written. The revision was flavoured with a sensitivity, empathy, and insightfulness that do credit to its author:

“We went to London and saw the bombings. You don’t have to look far. Buildings are down in nearly every block in Leicester Square and Piccadilly. We were there at night only so we’ll see more by daylight. London at night is beautiful. It is mysterious: a quietude that pulses – you can feel the life in the city rather than hear it. Without seeing it, it’s nearly impossible to see what a great city in a blackout is like. I love the blackout—now. Maybe I will change. People are going everywhere and there is a gaiety about it that can’t be explained ….”

Though raised in the sprawling metropolis of Chicago, Chuck was genuinely awestruck by the wonders of London.

“It is the first time”, he wrote, “that I’ve known what the ‘Heart’ of a city is. You can’t feel the pulse of a city with lights glaring everywhere.” He then went on to describe the Underground: “We took [it] to Leicester Square. There are long ramps running to the surface, high above the tunnel. Along these ramps, and on the train platforms, sleep the bombed-out of London. Cheerful, unbeaten, laughing, they share their company with other thousands of unfortunates. The floors are cement, the blankets make beds, and the homeless are at home. I felt ashamed when I passed that I was so comfortable, that Americans are so comfortable, that I hadn’t done something about it long before I did. Here you find the British citizen. It is pitiful yet heartening—you can’t exactly pity people like that: that would make you seem their superior—I was oh so humble walking past them. It’s not only adults either, but children—all ages, sleeping on the floor or playing. And yet it wasn’t they I felt sorry for, it was their mothers and fathers, destitute, and wondering where to turn. Two days later he told his wife that he had seen a raid that Saturday night. He called her Dearest Wifey. “the sirens are terrific and very eerie in the dark. We couldn’t see the Jerries, but we saw and heard the ak-ak fire and heard some bombs. I think they brought down six, if I’m not mistaken. After the sirens went, nearly everyone disappeared, but we stayed to watch the fun. It seemed more like a 4th of July celebration than an air raid. Nice clear night, but I guess the Jerries were too high to see and our eyes unaccustomed to looking for them.”

When Chuck departed Bournemouth on May 10th, Sergeant Holman was directed to a signal school presumably to enhance the wireless training he had received at Calgary. Finally, on 6th August, he was posted to RCAF 410 (Cougar) Squadron, based at RAF Drem in East Lothian, Scotland, a short distance from the Firth of Forth. Though officially Canadian, the squadron had been from the outset primarily manned by RAF personnel, pending the arrival of more Canadian air and ground crew. The quaint village of Drem, which could have stepped right out of the eighteenth century, likely afforded at least one watering hole for thirsty British and Commonwealth airmen.

RAF Drem, which boasted an innovative runway lighting system, was equipped with Boulton Paul Defiants, among other species of fighter aircraft, including the iconic Supermarine Spitfire of Battle of Britain fame. He would be assigned as a trainee airgunner aboard a Defiant, an unconventional fighter, which made up for its lack of frontal weapons by housing a powerful four-Browning machinegun turret immediately behind the pilot. Apart from this oddity, the aircraft bore a strong profile resemblance to its Drem companion, the Spitfire. In the early days of the war the Defiant had enjoyed considerable success, when it lethally surprised hapless German fighters attacking from the rear. Soon enough, however, Luftwaffe pilots tumbled to its unorthodox gun arrangement and attacked it head-on, sharply reducing its value as a daylight combat aircraft. Henceforth it was more successfully deployed as a night fighter during the Germans’ aerial “Blitz” on British cities.

As it turned out, the defensive sector for which 410 Squadron was responsible saw comparatively little action at this time, save for occasional “scrambles” to intercept possible Nazi “bandits”. As a consequence, Chuck’s flying was confined to orientation training exercises and he ended up experiencing no combat whatsoever. This state of affairs may have had some bearing on what occurred in the late summer and fall of 1941. Chuck found himself in hot water with camp authorities and was charged with misconduct and infraction of the rules, including “breaking out of camp” and absences without leave, which left a larger print than his earlier Regina misstep. He also ran afoul of the local civil constabulary, who arrested and briefly jailed him. His erratic behaviour begs some speculation. Apart from the gnawing tedium of camp life, did his innate dislike of bureaucracy, red tape and authority, traits noted by his nephew, Charles Wharton, contribute to the problem? Did a recurring sense of insecurity darken his outlook? More to the point perhaps, did he get some inkling of trouble in his marriage, as indeed there definitely would be a few months down the road? Whatever the answers to these questions, the upshot was his repatriation to Canada on 3 January 1942 and subsequent assignment to RCAF Rockcliffe (Ottawa). His days in the RCAF were clearly numbered. On 6th March 1942, after a transfer to RCAF Trenton, he was formally discharged.

All these events had unfolded against the backdrop of astounding developments half a world away that would shortly provide another twist to Chuck’s complicated life. On 7 December 1941, while he had still been at Drem, Japan had transformed the war by launching a devastating assault on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Now that his own country was in the fight, Chuck, within weeks of his RCAF discharge, made arrangements to enlist in the USAAF.

Meanwhile, what Chuck may have suspected in Scotland became a harsh reality. He was confronted with the unthinkable, the impending breakup of his marriage. He received the equivalent of a proverbial “Dear John” letter when he learned that Marie had filed for divorce and taken custody of Georgia and, moreover, denied his parents’ access to the child. Almost immediately after the divorce was finalized, Marie remarried, and her second husband formally adopted Georgia. In the circumstances it is reasonably safe to assume that the husband-to-be and Marie had become acquainted well before the final divorce papers were drawn up. The news must have spun Chuck into a new low just before his enlistment in the USAAF.

His sorry state of mind could not have been eased when he was advised that he would have to go to the end of the line as a cadet in the USAAF. Whatever he was obliged to tell his new masters about his chequered RCAF career will probably never be known because his US service record went up in smoke in a St. Louis repository. In any event, his need to start on the bottom rung again, coming on top of his marital woes, made for a rocky passage through his American training program. Though his official records were reduced to ashes, his family’s recollections and documents have galloped to the rescue. They reveal that on his second time around as a trainee he did not make air crew, even as an air gunner, his former stock in trade. The slide did not end there. He did not achieve the required results at his next training stop, a cookery school. In all likelihood, he did not, so to speak, fancy the menu.

Piercing the gloom, however, were some bright glows, notably his own remarriage to a Jo Sherman and a calming interlude spent as a lifeguard at a USAAF rest camp in New Braunfels, Texas. Finally, he scored a training success as a sheet metal worker, qualified to join a USAAF ordnance unit overseas, patching up damaged aircraft. On this, his second tour in Britain, he served at a USAAF facility (see insignia) in Ditchingham, a village and civil parish in Norfolk. There he joined a hundred other ground crewmen, most of whom were tasked with first, securing and then transporting bombs and other ordnance to outlying bases.

The unpredictable fates however, still had Chuck in their sights. In a blackout on 6 July 1944, while enjoying free time off the base, he was accidentally struck and killed by an ordinance supply truck. This was not an uncommon end for Allied service men, drivers and pedestrians alike, unfamiliar with British wartime rules of the road. It was a tragically ironic outcome for the grounded airman who had once been fascinated by his first experience of a blackout and its mystical effects.

At home, his wife Jo, who had been welcomed into the Holman family in Chicago, left to join an American Red Cross unit that served overseas. In turn, his father spent his 1944 sabbatical year touring US military bases under the auspices of the United Services Organization (USO) conducting seminars on pastoral counseling for Army and Navy chaplains. In the meantime, his service and death had been noted in the McMaster Alumni News, which scrupulously kept track of its constituency in the armed forces.

C.M Johnston & Lorna Johnston

NOTE: Readers who may have additional information or corrective suggestions are requested to get in touch at once with the authors: cjohnston12@cogeco.ca or 905 648-6272. All submissions will be gratefully acknowledged.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Once again Linda Payne deployed her admirable research skills to unearth vital information and productive leads. Robert Holman, Charles Wharton, and Annabel Wharton provided key family recollections and documentation. Also helpful were Julia Gardner (University of Chicago Library), Adam McCulloch (Canadian Baptist Archives) and Sheila Turcon (Special Collections, McMaster University Library).

SOURCES: National Archives of Canada, Record group 10: RCAF Service Record of Charles Montgomery Holman; Research Centre University of Chicago Library: Holman personal papers in the Jerald Brauer Papers: McMaster Divinity College/Canadian Baptist Archives: Student File and Biographical file of Charles Montgomery Holman; McMaster University Library/Special Collections: Marmor 1936, p.41, McMaster Alumni News, 12 Oct. 1944, p.1. Spencer Dunmore’s Wings for Victory: The Story of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan in Canada contains information on the training stations mentioned in the text.

Internet leads: RAF Drem, RCAF 410 Squadron, USAAF Airfields in Britain, Ditchingham.